Chocolate and Literature

A Rich History in Fact and Fiction

“Happiness is as simple as a glass of chocolate.” So wrote Joanne Harris in her bestselling novel Chocolat. But chocolate has not always been associated with simple pleasure alone. For the ancient Maya and Aztec civilizations, cacao was a sacred substance – used in royal rituals and often consumed as a bitter drink reserved for nobility. When European explorers like Hernán Cortés encountered chocolate in the 16th century, they brought it back to Europe, where it quickly captured the imagination of the elite. Over the centuries, chocolate’s story has unfolded both as factual history and as fertile ground for literary inspiration, taking on different metaphorical flavors in each era.

From Sacred Cacao to European Salons: Chocolate’s Early Journey

In Mesoamerica, chocolate was more than a treat – it was revered. The Maya and Aztecs prepared cacao as a spiced beverage, sometimes using it in ceremonies or as an offering to gods. This “food of the gods” (as the scientific name Theobroma cacao suggests) was valued for its invigorating effect. When the Spanish brought cocoa beans to Europe in the 1500s, they initially regarded it as a curious exotic import. By the early 17th century, however, Europeans had learned to mix ground cocoa with sugar, vanilla, and milk to create hot chocolate, transforming the bitter potion into a sweet delight. This new drink took root especially in Spain and later in the royal courts of France and England, where it became a fashionable indulgence among aristocrats.

As chocolate’s popularity spread through Europe, it also acquired a reputation for luxury and, intriguingly, for vice. In Baroque-era Europe, hot chocolate was believed to have medicinal properties and even aphrodisiac qualities. The wealthy would sip chocolate in exclusive coffee-houses and salons, establishments that were sometimes viewed with suspicion by moralists. In Restoration England, chocolate houses sprang up as upscale counterparts to the common coffeehouse. These elegant venues offered cups of rich chocolate alongside gossip, politics, and occasionally gambling. They became symbols of refined decadence – so much so that King Charles II, wary of political dissent brewing in coffee and chocolate houses, attempted to suppress them as hotbeds of sedition.

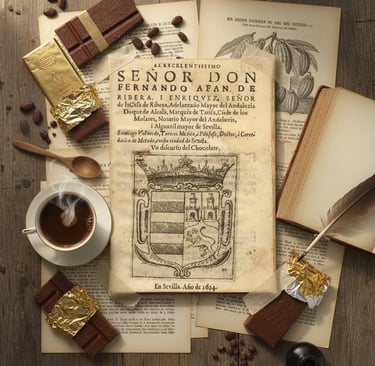

Not everyone embraced the chocolate craze. A few critics in the 17th century claimed that excessive consumption of chocolate could inflame passions or corrupt morals (one treatise even warned that monks should be forbidden from drinking it, lest it lead them astray). Despite such alarms, chocolate only grew in popularity. By the late 1600s, having a morning cup of chocolate was de rigueur for those who could afford it. It is in this period that chocolate made some of its earliest appearances in literature and letters. In 1671, the French aristocrat Madame de Sévigné famously wrote to her daughter about a pregnant acquaintance who drank so much chocolate that it might harm her unborn child – a mix of gossip and caution that illustrates how chocolate was viewed as both indulgence and potential danger.

Early Depictions of Chocolate in Literature

Literary works of the 17th and 18th centuries began reflecting chocolate’s complicated status in society. Playwrights and poets used chocolate symbolically to comment on fashion, excess, and social mores. For instance, English Restoration playwright William Congreve set a pivotal scene in The Way of the World (1700) in a chocolate-house. In this comedy of manners, the chocolate-house is depicted not as a den of political scheming but as a place of flirtation, frivolous chatter, and intrigue. Congreve’s choice of setting poked fun at the leisure pursuits of high society. One contemporary audience member even complained that the play had “no plot but many witty things to ridicule the Chocolate House” – indicating how closely chocolate was associated with the trendy, and perhaps superficial, pleasures of the time.

A few years later, in 1712, Alexander Pope cemented chocolate’s literary presence in his mock-epic poem The Rape of the Lock. This poem satirizes the vanity and decadence of the English aristocracy, and chocolate makes a memorable appearance. Pope describes fashionable ladies beginning their day with luxurious cups of hot chocolate. In one famous passage, the heroine Belinda is served chocolate in the morning by her maid, signaling her status and leisurely life. Pope writes: “And nymphs prepared their chocolate to take.” This vivid detail of aristocratic life – chocolate being as essential as the sunrise for the idle rich – underscores the theme of indulgence. Later in the poem, Pope even whimsically punishes a mythological character by condemning him to whirl in “fumes of burning chocolate,” blending humor with a hint of the exotic aura chocolate held at the time. Through Pope’s verses, we see how chocolate had become a metaphor for excess and luxury, a symbol instantly recognizable to his readers.

Across the Channel, similar trends were underway. In 18th-century Venice and Paris, literary cafés and salons were famous for serving chocolate alongside art and conversation. Enlightenment thinkers and writers frequented such cafés, fueling their debates with cups of chocolate. This atmosphere appears in the writings of philosophers and in the gossip of the day. Chocolate, once a colonial curiosity, had become an emblem of cosmopolitan sophistication in European culture – and literature duly noted this shift, portraying chocolate as the perfect companion to intellectual and amorous pursuits.

The 19th Century: Chocolate for the Masses and New Storytelling

The Industrial Revolution transformed chocolate from a luxury of the few to a treat for the many. In the 19th century, technological advances – such as the invention of the cocoa press in 1828 – made it easier to produce cocoa powder and solid chocolate in large quantities. Confectioners like J.S. Fry and Cadbury introduced the first chocolate bars and assorted chocolates by mid-century. As prices fell and chocolate became more widely available, it lost its exclusive status and became a beloved everyday sweet across social classes. Boxes of chocolates emerged as popular gifts, and enjoying a piece of chocolate became a commonplace pleasure rather than an exotic rarity.

This democratization of chocolate also found echoes in the literature of the era. Chocolate began appearing in novels and stories as part of ordinary life or a token of affection. While 19th-century literature may not have immortalized chocolate as flamboyantly as earlier satirists did, the presence of chocolate was felt in quieter ways. For example, in many Victorian novels and domestic tales, characters might offer a cup of hot cocoa to soothe someone, or a box of chocolates might figure as a courtship gift symbolizing love and indulgence. The term “chocolate-box” even entered the English language to describe something that is superficially attractive – derived from the sentimental Victorian habit of decorating chocolate gift boxes with idyllic images.

Writers of the time sometimes used chocolate to evoke comfort, warmth, or luxury in their narratives. In detective and mystery stories, a cup of cocoa might be offered to calm nerves on a dark night. Notably, in later years Agatha Christie would title one of Hercule Poirot’s cases “The Chocolate Box,” centering a mystery plot around a poisoned box of chocolates. Such references show that by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, chocolate had become ingrained in daily life and could serve as a literary device – whether as a comforting detail in a cozy scene or a key clue in a plot.

Chocolate in 20th Century Fiction: Fantasies, Symbols, and Magical Realism

In the twentieth century, chocolate took on new life in fiction, both as a delightful centerpiece and a layered symbol. One of the most iconic examples is Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), a children’s novel that brought chocolate to the forefront of imagination. Dahl, who himself had a lifelong love of sweets (and even recalled tasting chocolate samples as a schoolboy for Cadbury), created Willy Wonka’s fantastical chocolate factory – a wonderland of candy inventions and edible delights. The novel celebrates the joy of chocolate and candy, but also weaves in moral lessons about greed and humility. Here, chocolate is both literal – rivers of it flow through Wonka’s factory – and metaphorical, representing the rewards that await those pure of heart. Dahl’s story captivated generations and confirmed that chocolate, with all its allure, could inspire entire fictional worlds.

Beyond children’s literature, chocolate continued to serve as a potent symbol in adult fiction. Modernist literature occasionally noted chocolate in passing, grounding stories in the tactile details of everyday life. For instance, James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) includes scenes of ordinary Dubliners going about their day, and something as simple as cocoa or chocolates can appear amid the rich catalogue of mundane details, reflecting comfort and the colonial trade that brought such goods to Ireland. In the magical realist tradition, chocolate assumed a more central and evocative role. Gabriel García Márquez, in One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), touches on the presence of chocolate in the context of Latin American history and fantasy, hinting at its dual nature as a colonial import and a source of sensory pleasure.

Two late-20th-century novels, in particular, put chocolate at the heart of their narratives and titles. Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate (1989) uses food – notably chocolate – as a means of expressing emotion and enacting magical realism. Set in early 20th-century Mexico, each chapter of the novel opens with a recipe, and the characters’ deep feelings are transmitted through the dishes they prepare. The very title suggests something boiling with passion (in Spanish, “like water for chocolate” refers to water brought to a boil for making hot cocoa). In this story, chocolate symbolizes love, desire, and the passing down of tradition through recipes, blurring the line between the literal and the magical. Similarly, Joanne Harris’s Chocolat (1999) centers on a mysterious chocolatier who opens a confectionery in a conservative French village. Her luscious chocolates awaken joy and indulgence in the townspeople, challenging rigid social norms. In Harris’s tale, chocolate is a catalyst for change – representing temptation, pleasure, and liberation from repression – and each sweet treat is imbued with a hint of enchantment.

Even genre fiction and popular series incorporated chocolate’s beloved status into their worlds. For example, in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series (1997–2007), chocolate is given a small but memorable magical significance: characters eat chocolate to recover from the chilling effects of encounters with Dementors (dark creatures that drain hope and happiness). Rowling’s use of chocolate as a remedy for despair cleverly nods to the real-world comfort that chocolate provides. It exemplifies how deeply the idea of chocolate as a source of comfort has rooted itself in our collective imagination.

A Legacy in Fact and Fiction

From its ancient ceremonial origins to its role in modern bestsellers, chocolate’s journey is a rich tapestry woven through both fact and fiction. Historically, chocolate transformed from a sacred bitter drink into a global sweet commodity, and each stage of that transformation left a mark on culture and literature. Writers in every age have found inspiration in chocolate’s richness – whether to critique the excesses of the powerful, to revel in the delights of the senses, or to explore themes of love, temptation, and comfort.

What makes chocolate such an enduring motif in literature is its dual nature. It is a tangible treat, a product of historical conquest and commerce, but it also carries a mystique and emotional resonance far beyond its taste. Chocolate can signify luxury, as it did for the aristocrats of Pope’s time; it can symbolize care and affection, as in a gift between lovers or a soothing cup given to a weary soul; and it can even stand for personal transformation and freedom, as seen in modern novels where characters reinvent themselves through the simple act of sharing a chocolate.

In fact and in fiction, chocolate has been consistently linked to desire and delight. It engages all the senses – much like a good story does. Perhaps that is why authors and readers alike are drawn to it. The history of chocolate is filled with intrigue, innovation, and change, and those qualities make it ripe for storytelling. Likewise, stories about chocolate often reflect real human longings and social dynamics, whether in a 17th-century play or a contemporary magical tale.

As we look back on the centuries, it’s clear that chocolate and literature have been deliciously intertwined. Chocolate’s real journey from rainforest cacao pods to European salons to every supermarket shelf parallels its literary journey from the pages of Enlightenment satire to children’s fantasies and beyond. Each enriches the other: literature gives chocolate a deeper meaning beyond flavor, and chocolate gives literature a tangible, universally beloved symbol to work with. This timeless pairing of chocolate and storytelling continues to enchant us, reminding us that even something as simple as a sweet can carry a rich history and inspire countless imaginations.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!