From Sacred Drink to Global Obsession

The Extraordinary 4,000-Year Journey of Chocolate

Chocolate. Just the word alone can summon the velvety taste on the tongue and the comfort of a beloved treat. But long before it was molded into bars and bonbons, chocolate was something else entirely: a sacred drink, a bitter medicine, a currency, an obsession. Its story spans over four millennia, beginning in misty ancient jungles and reaching into every corner of our modern world. It’s a journey of ritual and conquest, of innovation and indulgence. Let us travel back to where it all began — to a time when chocolate was revered as the “food of the gods” — and trace its remarkable evolution from sacred brew to global obsession.

The Sacred Brew of the Gods

In the lush rainforests of ancient Mesoamerica, a circle of elders gathers around a fire. A clay vessel passes from hand to hand, filled with a dark, frothy liquid. The aroma is earthy and spiced, redolent of roasted cacao beans and wild vanilla. This is chocolate in its primal form — a far cry from any sweet confection we know today. For these people, the Olmec and later the Maya and Aztec, this bitter elixir is nothing less than a gift from the gods.

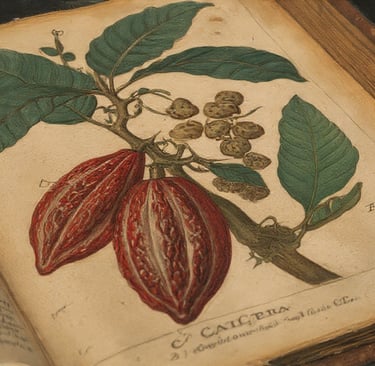

Thousands of years ago, the Olmec civilization in what is now southern Mexico first unlocked the secrets of the cacao tree. They discovered that the seeds inside the cacao pod, if fermented, roasted, and ground, could be whipped into a potent drink. We have no written records from the Olmecs, but archaeologists have found their stone vessels stained with telltale traces of theobromine — the chemical stimulant in cacao that hints at ancient chocolate recipes. It’s likely the Olmecs used cacao in ceremonial drinks as early as 1500 BCE, establishing a tradition that would flourish in later cultures.

The Maya, inheritors of this knowledge, elevated cacao to divine status. In Mayan society (circa 250–900 CE), chocolate was central to life — not an everyday candy, but a sacred and social centerpiece. Imagine a grand Mayan feast: nobles and priests sipping cacao from painted pottery cups, the liquid frothed by pouring it back and forth until a delicate foam crowns the surface. They often blended the bitter cacao with spices like chili pepper, allspice, or a touch of honey to soften its bite. In the glow of flickering torches, cacao drinks would be shared during important ceremonies, marriages, and even rites of passage. One ancient Mayan phrase, chokola’j, meaning “to drink chocolate together,” hints at the communal joy of sharing this sacred brew.

To the Maya, and later the Aztecs, chocolate was imbued with spiritual meaning. It was used as an offering in rituals — sometimes colored red with annatto to symbolize blood — and was believed to carry the essence of life. They associated it with deities: the Maya honored a cacao god (Ek Chuah in some accounts), and the Aztec believed the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl had journeyed from paradise to deliver cacao to humankind. In fact, the Latin name given to the cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, literally means “food of the gods,” reflecting these ancient reverences.

Cacao beans were not only eaten and drunk; they were treasured as currency. In bustling Mayan marketplaces and Aztec bazaars, people traded with cacao beans as money. A few dozen beans might buy you a cloth or a turkey hen in the Aztec Empire. So prized were these seeds that counterfeiters in ancient times even forged fake cacao beans out of clay. A Spanish chronicler in the 16th century marveled that in the Aztec realm, “cacao beans were more valuable than gold.”

For the Aztecs of central Mexico (14th–16th century), chocolate was mostly reserved for nobility, warriors, and priests — a luxurious indulgence with a reputation for giving energy and vitality. Aztec chocolate, known in the Nahuatl language as xocoatl (meaning “bitter water”), was typically served cold and unsweetened, often flavored with spices or fragrant flowers. One legendary account claims the emperor Montezuma II would ceremonially drink 50 golden goblets of chocolate a day, especially to fortify himself before visiting his harem. (More likely, this is an exaggeration — fifty cups of cacao would challenge even the hardiest chocoholic — but the story speaks to chocolate’s aura as an aphrodisiac and strength-giver.) To the Spanish who would soon arrive, this exotic beverage was unlike anything in Europe: dense, bitter, sometimes spiced with chili, and served with a naturally frothy head from vigorous mixing. Little did those Europeans know that this strange dark drink was about to take them by storm, sparking a global passion that burns bright even today.

Conquest and Cocoa: Chocolate Meets the Old World

In the year 1519, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his entourage stood in the splendid court of Montezuma in Tenochtitlán (present-day Mexico City). Among the many wonders of the Aztec capital, one caught the Spaniards by surprise: they were served an unfamiliar dark potion in ornate cups. It was xocoatl, the spiced cacao brew. Some of Cortés’s men found it bitter and unpalatable at first sip — one described it as more fit for pigs than people — but they noted how the Aztecs esteemed it. Cortés himself observed that this “divine drink… builds up resistance and fights fatigue,” hinting at the energizing kick of the cacao. After the bloody conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521, Cortés and the Spanish settlers in the New World realized that, beyond gold and silver, they had stumbled upon another treasure in cacao.

By the 1540s, cacao beans and recipes for making chocolate had begun making their way back to Spain. Legend has it that the first samples reached Europe when Dominican friars brought a delegation of Mayan nobles to visit Prince Philip of Spain — presenting cacao as part of the tribute. Another tale suggests Cortés himself presented cacao beans to King Charles V. However it arrived, one thing is certain: once chocolate touched Spanish lips, it ignited curiosity. The Spanish conquistadors learned to prepare the drink but quickly adapted it to suit European tastes. They served it hot rather than cold, and crucially, they sweetened it with cane sugar (a crop they were already bringing from the Old World to plantations in the New). They also toned down the chili and instead added comforting Old World spices like cinnamon, anise, or vanilla. The result was a rich, warm, sweet chocolate beverage that bore little resemblance to the bitter Aztec brew beyond its core ingredient.

At first, Spain kept chocolate a secret indulgence — a delightful court luxury guarded closely. Throughout the late 1500s, Spanish aristocrats and clergy developed a fervor for hot chocolate, sipping it from fine porcelain cups. A cup of hot cocoa became the morning ritual of the nobility in Madrid, enjoyed with a dunk of bread or a slice of sponge cake. In convents and monasteries across Spain, nuns and monks found that a dose of chocolate helped them endure long fasts and prayer vigils (much to the dismay of some strict Church authorities). In fact, chocolate soon spurred a theological debate: does drinking chocolate break the holy fast or is it permissible? This question was hotly discussed until one learned Cardinal pronounced the famous verdict, “Liquidum non frangit jejunum” – liquid doesn’t break the fast, giving the Church’s blessing to the chocolate habit (at least as a drink).

By the early 1600s, the secret was out. Chocolate began to spread across Europe, riding on the currents of trade and marriage. Italian merchants in places like Florence and Venice caught wind of the fashionable new drink and brought cacao home. A watershed moment came in 1615, when the Spanish princess Anne of Austria (a Habsburg who was actually raised in Spain) married King Louis XIII of France. She brought with her a dowry of cacao and a love of chocolate, introducing the French court at Versailles to the beloved beverage. Later, King Louis XIV’s Spanish wife, Maria Theresa, would also champion chocolate at the Sun King’s sumptuous court, further securing its status as the drink of royalty. France’s elite fell under chocolate’s spell; it was said to be enjoyed by Madame de Pompadour and even Marie Antoinette, who had a personal chocolatier prepare concoctions laced with exotic spices or amber to boost her health and libido.

Courts, Cafés, and Controversy: Chocolate Conquers Europe

Once chocolate made its debut in Europe, it evolved from an exotic curiosity into a full-blown cultural craze. In the 17th and 18th centuries, chocolate was the height of fashion among Europe’s aristocracy. It was no longer confined to Spanish courts; by mid-1600s, chocolate had swept into Italy, Austria, France, and beyond. European palates, once dubious, had acquired a lust for the rich new beverage — provided it was loaded with sugar and aromas.

Chocolate houses began popping up in the great cities of Europe, paralleling the rise of coffeehouses. The first known chocolate house in London opened in 1657 on Bishopsgate Street, advertised as an “excellent West India drink.” There, for an exorbitant price, London’s well-heeled could sip hot chocolate and socialize. These establishments quickly became chic gathering spots for intellection and gossip; political schemers, poets, and dandies alike conducted lively debates and card games with steaming cups of chocolate at hand. In time, some of these chocolate houses (such as White’s and Brooke’s in London) evolved into exclusive gentlemen’s clubs. Across the Channel, Paris had its own salons de chocolat, where the elite delighted in the stimulating drink served in fine china, often accompanied by buttery pastries.

Chocolate’s rise was not without controversy. Some conservative voices in Europe’s religious circles initially scorned chocolate as sinful or decadent — after all, it came from “pagan” lands and was often consumed with a near-addictive zeal. There were whispers that chocolate might inflame passions or that it was a drug-like indulgence. In one famous case, some austere monks in Spain tried to ban chocolate within their monasteries, deeming it a threat to spiritual discipline (perhaps because some monks were sneaking cups of cocoa to stay awake during services!). But such resistance was fleeting. In most places, the delight of chocolate won out over any moral qualms. By late 1600s, even the Jesuits were involved in cacao trade and production in their missions, effectively becoming chocolate’s promoters.

As chocolate integrated into European life, etiquette and innovation blossomed around it. Special vessels and serving ware were devised to enhance the chocolate experience: elegant porcelain cups, often with lids to keep the chocolate warm, and saucers called mancerinas designed to hold those cups without spilling the precious liquid. Aristocratic ladies were said to carry small flasks of chocolate to church to sip during long sermons (until the practice was banned for being too distracting from the Word of God!). Recipes, too, were elaborated. Cooks invented chocolate pastries, custards, and even early forms of solid treats. In eighteenth-century France, chefs crafted a predecessor to chocolate mousse (aptly called “chocolate foam” back then). The first instances of chocolate being paired with milk or used as a flavor in cakes and candies date to this era as well.

Through the 1700s, chocolate remained a luxury indulgence, expensive and labor-intensive to produce. Its consumption was largely for the rich and well-connected. But beyond the gilded palaces and cafés, another story was unfolding — one of supply and demand that would have global repercussions. To satisfy Europe’s growing chocolate obsession, colonial powers dramatically expanded cacao cultivation. Cacao trees, native to the Americas, were transplanted to tropical colonies: the Spanish grew them in Venezuela, Ecuador, and the Caribbean; the Dutch planted them in Indonesia; the French in the Caribbean and West Africa; the Portuguese in Brazil and later Africa as well. This expansion was built on the backs of the enslaved and indigenous peoples forced to farm the precious beans. By the eighteenth century, chocolate was big business, and like sugar, it thrived on the exploitative economies of the colonial plantation system. While fashionable ladies and gentlemen savored sweet chocolate in porcelain cups, countless laborers in equatorial fields toiled under harsh conditions to tend the fragile cacao trees and hand-process the beans. This dark side of chocolate’s history was a bitter reality underlying its rise as a global commodity.

From Elixir to Confection: The Industrial Chocolate Revolution

For centuries, chocolate was primarily consumed as a drink — albeit one associated with power, wealth, and ceremony. That began to change in the 19th century. The era of steam engines and innovation did not pass chocolate by; in fact, it transformed chocolate from a costly elixir of the elite into a treat affordable to the masses. This was nothing short of a revolution in the world of chocolate, driven by curiosity, entrepreneurship, and a bit of scientific wizardry.

One of the first breakthroughs came in 1828 in the Netherlands, when a chemist named Coenraad van Houten patented a new process for cacao. Van Houten’s method used a simple hydraulic press to squeeze out much of the cacao’s natural fat (cacao butter) from roasted beans. The result was twofold: a cake of dry cocoa that could be pulverized into a fine cocoa powder, and a separate reserve of cacao butter. This process, along with an alkalizing technique he introduced (dubbed “Dutching”), made it far easier to mix chocolate with water or milk, and it greatly improved the consistency and reduced the bitterness of the drink. More importantly, by reducing the fat content to get cocoa powder, Van Houten paved the way for solid chocolate: Confectioners realized they could recombine cocoa powder with just the right amount of cocoa butter and sugar to create a paste that would solidify into a bar. Chocolate was ready to burst out of the cup and into a handheld form.

The next milestone arrived in 1847 in England. An enterprising chocolate maker named Joseph Fry mixed cocoa powder, sugar, and melted cacao butter, and poured it into a mold. It hardened into what we recognize as the world’s first true chocolate bar. By modern standards, Fry’s chocolate bar was coarse and gritty, but to Victorian consumers, it was a marvel — chocolate you could actually bite into! Soon, competitors like the Cadbury brothers in Britain were also producing molded “eating chocolate,” and a new market for solid confections was born.

In Switzerland, the chocolate revolution continued. In 1875, Swiss chocolatier Daniel Peter perfected the recipe for milk chocolate. For years he had experimented with adding milk to chocolate to mellow its strong taste. With the help of his friend and neighbor, Henri Nestlé (who had invented a method to make powdered milk), Peter combined condensed milk with chocolate liquor and sugar to create a smoother, creamier chocolate that had a lighter color and a gentler taste. Milk chocolate was an instant hit and would eventually become the world’s favorite type of chocolate. A few years later, another Swiss innovator, Rudolf Lindt, invented the conching machine (in 1879), a device that stirred and aerated molten chocolate for hours (or days) to refine its texture and flavor. Lindt’s conching produced silky, melt-in-your-mouth chocolate and solved the problem of earlier bars being somewhat grainy or hard. Thanks to Lindt, chocolate could now be silky smooth.

The late 19th century also saw the rise of chocolate dynasties — family-founded companies that still dominate the chocolate world today. The Cadburys in England, the Mars and Hershey companies in America, the Nestlé empire, Lindt in Switzerland, and Ferrero in Italy all have their roots in this era from the 1850s to early 1900s. These companies harnessed industrial processes to roast, grind, press, conch, and mold chocolate on a scale previously unimaginable. By the turn of the 20th century, chocolate had been democratized. No longer a rare luxury, it was being produced en masse in factories, wrapped in bright papers, and sold for a few pennies. Children could spend their allowance on a chocolate bar; soldiers carried chocolate rations for energy in the field (during the American Revolutionary War, and famously again in World War II); and ordinary families could share a box of affordable chocolates on special occasions.

Yet even as chocolate became a sweet symbol of the Industrial Age, the expansion of its production had global ripple effects. With Europe’s appetite for chocolate growing exponentially, the sourcing of cacao expanded further into the tropics. Colonial powers established huge cacao plantations in Africa and Asia. Notably, by the late 1800s, cacao farms in West Africa (in places like the Gold Coast, today’s Ghana, and Ivory Coast) were gearing up to supply ever more cocoa. Tragically, many of these operations relied on forced labor or indentured servitude. In islands like São Tomé and Príncipe, Portuguese plantations in the early 1900s were exposed for using enslaved workers to grow cacao, causing an international scandal that pushed British firms like Cadbury to seek more ethical sources. The economic dimension of chocolate’s triumph was double-edged: fortunes were made in Europe and North America selling chocolate confections, while far away, farmers and laborers struggled, often impoverished and exploited, to produce the raw cocoa that fed this booming industry. It was a bittersweet legacy that would later spur movements for fair-trade and ethical cocoa sourcing in the decades to come.

A Global Obsession: Chocolate’s Modern Legacy

As the 20th century unfurled, chocolate became not just a treat, but a global cultural icon. Its influence is everywhere — in our holidays, our language, our cravings, our memories. Consider the traditions: heart-shaped chocolates on Valentine’s Day (a practice popularized by Richard Cadbury’s fancy chocolate boxes in the late 1800s), foil-wrapped eggs and bunnies at Easter, or a steaming cup of hot cocoa on a winter’s night. By mid-century, a world without chocolate was unimaginable. It had conquered every continent, every society, from the sweet shops of Paris to the stalls of Mumbai, from high-end Swiss chocolatiers crafting pralines to convenience stores in Midwest America selling candy bars by the dozen.

Part of chocolate’s modern allure is sensory and emotional. Scientifically, we know that eating chocolate releases endorphins and stimulates pleasure centers in the brain — there’s chemistry behind that blissful feeling. Culturally, chocolate symbolizes comfort, love, indulgence, even reward. Think of the simple joy of unwrapping a bar and snapping off a piece, the satisfying “snap” sound of tempered chocolate breaking, the way it starts to melt between your fingers if you don’t get it to your mouth fast enough, and then the flood of flavor as it dissolves on your tongue. Whether it’s a humble milk chocolate bar that reminds someone of childhood or a single-origin dark chocolate tasting square savored by a connoisseur, chocolate evokes passion like no other food. We call ourselves “chocoholics” half-jokingly, but the term “chocolate obsession” isn’t far from truth for many.

By the numbers, our modern appetite for chocolate is astounding. The world now consumes millions of tons of cocoa beans each year. In an average year, the average Swiss citizen (world leaders in chocolate eating) might devour nearly twenty pounds of chocolate, and many other countries are not far behind. Global chocolate sales reach tens of billions of dollars annually. This humble bean, once brewed by Maya priests for sacred rituals, is now the foundation of a vast global industry. It fuels economies of entire nations in West Africa and Latin America where cacao is a key export. It’s traded in international commodity markets. And the big chocolate brands have become household names across continents.

Yet even as chocolate pervades daily life, in some ways it is circling back to its roots. In recent years, there’s been a growing appreciation for chocolate’s heritage and craft. Just as wine lovers trace vintages, chocolate lovers now seek out single-origin chocolates, reveling in the distinct notes a cacao from Madagascar might have versus one from Ghana. Small “bean-to-bar” artisans have sprung up, devoted to sourcing high-quality beans directly from farmers and roasting and crafting chocolate in small batches, often highlighting the very notes of fruits or flowers that ancient chocolate drinkers might have tasted in their brews. Some modern enthusiasts even participate in cacao ceremonies, harking back to the drink’s spiritual beginnings, consuming bitter hot cacao in meditative group rituals intended to foster mindfulness and connection — a direct nod to chocolate’s mystical past.

The story of chocolate also continues to evolve in terms of equity and sustainability. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen consumers and activists push for fair trade cocoa, seeking to ensure that the farmers who cultivate this beloved crop are paid fairly and work in humane conditions, and that the environment (so crucial for cacao, which grows only in particular tropical climates) is protected. Major chocolate companies have been pressured to address issues like child labor in cacao farming and to adopt more sustainable practices. So, the journey of chocolate is not just a tale of delight; it’s also a mirror to global issues of trade, fairness, and environmental care.

After 4,000 years, chocolate still holds a dual identity. It is a modern mass-produced commodity, found in the humblest vending machines and the grandest boutique windows. It is at once cheap and ubiquitous, yet also capable of being refined into a luxury experience. We bake with it, we snack on it, we celebrate with it. And yet, peel back the foil, close your eyes as a piece of chocolate melts in your mouth, and you just might sense a flicker of its ancient soul. You might imagine, even if only for a moment, an echo of that first cacao brew sipped in a sacred grove long ago, or the toast of an aristocrat raising a porcelain cup to their lips in a gilded hall.

From sacred drink to global obsession, chocolate’s journey is extraordinary not just for its length, but for how deeply it has touched humanity at every step. A simple bean, once worshipped and fought over, has become a source of simple pleasure for billions. In each creamy, sweet, dark, or spicy taste, chocolate carries with it a rich legacy — the prayers of priests, the ambitions of conquerors, the dreams of inventors, and the delights of everyday people. As we savor our next bite, we partake in this epic story, a small square of the world’s history dissolving on the tongue, connecting us through time with all the other chocolate lovers who came before.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!