The Bitter Code

How a Cup of Chocolate Helped Crack Early Cryptography and Secret Communication

Imagine a dimly lit London salon in the 1700s: the air is rich with the scent of hot chocolate and candle smoke as gentlemen huddle in a corner, whispering treason. Fast forward to World War II, and a young codebreaker at Bletchley Park scribbles furiously on a chocolate bar wrapper, racing to decode a Nazi message. Throughout history, chocolate has been more than a sweet treat or luxury indulgence – it’s been an accomplice in espionage, a cover for clandestine plots, and even a weapon in disguise. This is the little-known story of how a simple cup of cacao became entwined with secret messages and cryptographic breakthroughs, a tale where Sherlock Holmes meets The Imitation Game, but edible.

Cacao Couriers and Colonial Secrets

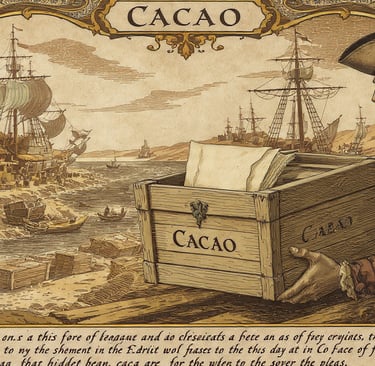

Our journey begins in the age of empires. In the 16th and 17th centuries, chocolate was a secret the Spanish Empire tried desperately to keep. After conquistadors brought cocoa beans from the New World, Spain held a monopoly on this exotic product. For nearly a hundred years, tasting chocolate was a privilege of Spanish nobility and monks sworn to silence. It was said that Spain guarded the preparation of cacao as if it were state espionage – and in a sense, it was. Controlling chocolate meant controlling a lucrative trade and a source of power.

But secrets rarely stay buried. By the 1600s, rival European powers and opportunistic smugglers were scheming to get their hands on cacao. Enter the courier networks and merchant spies: agents who realized that a shipment of cacao could double as a stealth messaging service. Sacks of cocoa beans became an ideal cover to hide letters or ciphered documents; after all, who would suspect mundane cocoa of concealing treason? In ports and marketplaces from Veracruz to Seville, barrels labeled “cacao” might contain hidden correspondence nestled among the beans. Merchants, pirates, and monks alike learned that a few sheets of parchment could be slipped under a false bottom of a crate or inside a hardened cake of chocolate, safely ferrying secrets across oceans.

Sidebar – The Pirate Who Burned a Chocolate Fortune: In 1579, English privateer Sir Francis Drake captured a Spanish ship expecting chests of gold and silver. Instead, his crew found tons of strange, dark beans in the hold. Mistaking the cacao beans for worthless “sheep droppings,” the frustrated pirates burned the entire cargo. Little did they know they’d just incinerated a small fortune in chocolate – and helped Spain keep its prized secret a little while longer.

Smuggling and subterfuge soon followed the chocolate trade. By the 1700s, a thriving black market saw Dutch, English, and French traders covertly ferrying cacao out of Spanish colonies. In one notorious scandal, Jesuit missionaries in Peru were accused of hiding gold nuggets inside solid cacao paste they shipped to Europe – a literal golden center in a chocolate shell. The scheme enriched their cause and spawned a catchphrase in Spain: something exceptionally heavy was “heavier on the stomach than Jesuit-made chocolate.” It was a sly reference to the contraband gold bars adding weight to the convents’ cocoa shipments. Here was chocolate not only funding secret missions, but physically hiding them as well.

These early chapters set the stage for chocolate as a vehicle of secrecy. A simple sack of cocoa could slip past checkpoints better than a satchel of letters marked “Top Secret.” Whether tucked in a merchant’s caravan or a ship’s cargo hold, chocolate became a trusty cloak-and-dagger tool – delicious to consume, and even more useful to conceal.

Hot Chocolate and Hotbeds of Sedition

As chocolate migrated into Europe’s elite circles, it found a new role: lubricating the plots and schemes of revolutionaries. Nowhere was this more evident than in the famed chocolate houses of 17th and 18th century London. These were fashionable gentlemen’s clubs where the wealthy sipped premium hot chocolate and gossiped – or, just as often, conspired. The brew in their porcelain cups might be sweetened with sugar and cinnamon, but the talk could turn bitter with treason.

London’s chocolate houses quickly gained a reputation as political hives. The most exclusive establishments – White’s, Ozinda’s, and The Cocoa Tree – catered to nobles and high-rollers. Ostensibly they gathered to enjoy “exotic” cocoa drinks, but behind closed doors much more was stewing. Different houses aligned with rival factions: White’s became a Tory stronghold, while Whig politicians socialized at Brooks’s. The Cocoa Tree on St. James’s Street, in particular, was notorious as a meeting spot for Jacobites – supporters of the exiled Stuart king. So prevalent was seditious talk there that The Cocoa Tree reportedly even had a secret escape tunnel, a “bolt hole” leading to a back alley, allowing plotters to flee whenever the King’s officers came knocking.

"Hotbeds of sedition!" fumed King Charles II, condemning London’s unruly chocolate houses where political plots brewed along with the cocoa.

The king’s epithet was not hyperbole. In 1715, during one Jacobite uprising, a group of rebels were literally arrested while nursing cups of chocolate at Ozinda’s Chocolate House, caught red-handed in mid-conspiracy. At these establishments, one might exchange furtive whispers about restoring the Catholic Stuarts to the throne, all under the guise of a genteel social drink. In an era before phones or the internet, a busy chocolate salon was the perfect cover for intelligence agents and dissidents to meet face-to-face. Spies of the day mingled with nobles, eavesdropping on whispers of revolt over the clink of china cups.

Even the beverage itself took on political symbolism. To many loyalists, “drinking chocolate” in certain circles became shorthand for Jacobite sympathies. Fashionable ladies and gentlemen might demurely say they were going out for chocolate, but that could be code implying a rendezvous to swap radical ideas. As one historian noted, at the height of tension “to sip chocolate was to court sedition.” In those boisterous chocolate dens, the line between café society and spycraft blurred. One could argue that modern intelligence culture – the art of gathering secrets in plain sight – was foreshadowed by those cocoa-fueled meetings. The next time you enjoy a hot chocolate, picture radical ideas and clandestine alliances swirling in the cup – as they often did in eighteenth-century London.

Hidden Messages and Smugglers’ Tricks

Not all secret chocolate operations happened in grand salons. Some took place on the high seas and in colonial warehouses, where smugglers and couriers honed crafty methods to hide information inside chocolate itself. If the previous era was about talking conspiracies over chocolate, this one was about encoding conspiracies into chocolate.

One clever technique involved using hardened chocolate or cocoa butter as a physical medium for messages. For example, a courier carrying an incriminating letter might bury it in a block of pressed cacao, the kind used to make drinking chocolate. The letter, wrapped in oilskin, would be shoved into a hollowed-out portion of the solid cocoa cake, then resealed. To any inspector, it looked like an ordinary brick of chocolate – nothing worth confiscating (besides, who would destroy such a luxury on a hunch?). Once safely delivered, the recipient could melt the cacao block and extract the hidden note. In an age when wax tablets and carved ivory were also used to conceal writings, chocolate was just another ingenious vehicle for steganography, the art of secret hiding places.

Smugglers, too, found chocolate useful for concealing codes and signals. A sack of cocoa beans might include a few odd items that carried meaning to those in the know – perhaps a uniquely marked bean or a paper with a sequence of cacao trading numbers that actually corresponded to a secret rendezvous date. Some colonial records hint that pirate crews developed simple ciphers based on cocoa cargo counts (“shipments of X beans” as code for amounts of gunpowder or troops). And in the age of high piracy, more than one undercover agent posed as a cacao trader to slip in and out of ports undetected. After all, a merchant bargaining over cocoa aroused less suspicion than a diplomat carrying letters.

Chocolate even intersected with religious secrecy and identity. In the Spanish Inquisition era, secret Jews (crypto-Jews) living in New Spain would sometimes use chocolate as a kind of cultural code. Records tell of a noblewoman in Mexico who offered a visitor a cup of chocolate; when he refused to drink it (perhaps fearing it wasn’t kosher), she instantly realized he shared her hidden faith. A simple chocolate refusal became a covert handshake, identifying friend from foe without a word spoken. In this way, chocolate’s role as a social staple made it an unlikely cipher for signaling insider status among the persecuted – a sweet stand-in for a secret handshake.

From colonial smugglers hiding gold and letters in cacao sacks to subversive signals stirred into hot cocoa, the humble cacao bean carried a lot more than flavor. It carried information – and sometimes the fate of empires – within its bitter, unassuming shell.

War and Peace Through Chocolate

By the 20th century, chocolate had earned a place in every soldier’s ration kit and every civilian’s heart. It was energy, comfort, and a taste of home. But even on the brutal front lines of world wars, chocolate continued its secret double life – boosting morale in the clear light of day, and trading in subterfuge after dark.

One of the most touching episodes came during World War I. In December 1914, the city of York in England sent special tins of chocolate to all its sons fighting on the front as Christmas presents. The effect was magical. War-weary Yorkshire lads in trenches and training camps savored the unexpected gift – a moment of sweetness amid the mud and misery. In return, over 250 of them penned thankful replies, letters so heartfelt they earned a nickname: the “Chocolate Letters.” These letters, preserved by the York museum, speak to how a simple treat can carry profound emotional messages. “I feel I ought to send my very best thanks for the nice box of chocolate I received so unexpectedly,” one soldier wrote from the front, before closing with a line that tugs at the heart even a century later:

"I shall prize the box as long as God spares me." – Gunner Henry Bailey, in a 1915 letter thanking his hometown for a gift of chocolate.

These were not coded messages in the cryptographic sense, but they were messages borne of chocolate nonetheless – notes of hope and gratitude riding on the coattails of a candy tin. The people of York had effectively used chocolate as a communication medium to boost morale, and the soldiers’ replies showed how powerful that gesture had been.

World War II, however, shifted the scene from heartfelt letters to deadly intrigue. The same war that produced Alan Turing and the Enigma codebreakers also produced one of the most bizarre espionage gadgets in history: the exploding chocolate bar. In 1943, British intelligence MI5 uncovered a Nazi plot so diabolical it sounded like a dark fairytale. German saboteurs had designed an apparently ordinary chocolate bar – black foil wrapping, gold lettering and all – that concealed a slab of high explosive. If an unsuspecting British VIP (perhaps Winston Churchill, known for his sweet tooth) tried to snap a piece off, a hidden charge would ignite after a seven-second fuse, blowing the chocolate – and the eater – to pieces. Codenamed the “Peter’s Chocolate” bomb, this weapon was a testament to how literally explosive chocolate’s role in warfare had become. Thankfully, Allied spies foiled the plan before the lethal candy bar ever found its way to Churchill’s desk. But the mere existence of such a device proved that in war, even innocent confectionery could not be trusted. “Death by chocolate,” usually a joking phrase, was suddenly a very real threat.

Sidebar – Death by Chocolate: The Nazi chocolate bomb uncovered in WWII was as devious as it sounds. Under the chocolate coating was a steel bomb filled with explosives. It was designed to detonate when a piece was broken off. British agent Victor Rothschild, tasked with counter-sabotage, commissioned detailed sketches of the device so his team could recognize and disarm it. Thanks to those efforts, “Peter’s Chocolate” never got the chance to turn dessert into disaster.

Allied forces, for their part, used chocolate in more benevolent covert ways. American and British commanders sometimes hid escape tools inside chocolate bars shipped to POWs – a compass here, a tiny file there – banking on the enemy’s obliviousness or the prisoners’ resourcefulness. And on the home front, British candy manufacturers developed unappetizing high-cocoa bars (ironically called “Excellence” or “Special Chocolate”) as part of survival kits for agents in the field. These bars were so bitter and dense that you’d only eat them in an absolute emergency – which made them perfect for secret messages too. A spy could scratch a note on the hard surface of such a bar or use its unwrapped foil as signal mirror, then simply eat the evidence if danger approached. Chocolate had become standard issue gear for the shadow warriors of WWII.

Cracking Codes Over Cocoa

Amid all these clandestine uses of chocolate, perhaps its most surprising role was in pure cryptography – the science of secret codes. The image of bespectacled codebreakers poring over strange ciphers might seem worlds away from anything as frivolous as chocolate. But at Bletchley Park, the top-secret British codebreaking center during World War II, the worlds of sweet cocoa and high mathematics did intersect. Long, grueling hours deciphering enemy communications required quick energy and comfort, and the staff famously guzzled endless cups of tea. Less famous is the fact that chocolate bars were a prized snack among the codebreakers – a little sugar boost to keep the brain whirring during a midnight shift decoding Enigma ciphers.

One young woman at Bletchley, however, found chocolate useful for more than staving off hunger. Mavis Batey, a 19-year-old cryptanalyst, made history in 1941 by cracking a crucial Italian naval code, helping set up the Royal Navy’s victory at Matapan. But her legend includes a quirky detail: according to later accounts, Mavis had so few writing supplies on hand during one breakthrough moment that she grabbed the wrapper of a chocolate bar on her desk and began scrawling down preliminary decryptions on the foil. Whether by coincidence or fate, that chocolate-fueled effort paid off – she deciphered the message in record time (just minutes), giving the Allies vital information about an impending Italian attack. The tale of the chocolate wrapper code-crack became part of Bletchley lore, a reminder that genius can improvise with whatever materials are at hand. In Mavis’s case, a late-night candy bar turned into an unlikely decryption pad that helped change the course of the war.

The connections didn’t end there. In the later stages of WWII, British codebreakers were hunting for any edge to break the latest German ciphers. One idea hatched involved printing subtle code hints on the packaging of soldier’s rations, including chocolate. The notion was to embed a string of seemingly random letters or patterns on a chocolate bar wrapper, which Allied soldiers in the field would recognize as guidance for using a new cipher system (but to the enemy, it looked like part of the design or an innocuous lot number). There are hints in declassified files that some British special ops units received maps or coded instructions concealed in the labels of their ration chocolates. If captured, the enemy might devour the chocolate and discard the wrapper none the wiser, while the Allied trooper had already memorized the hidden message. It was low-tech steganography – hiding secrets in plain sight – and chocolate was an ideal delivery vehicle. After all, who would suspect a candy wrapper of carrying military intelligence?

In the annals of cryptography, such tricks are a footnote compared to the famous Enigma machine or Navajo code talkers. But they illustrate an important point: the craft of secret communication often exploits the everyday and ordinary. A coded message on elegant stationery screams “important – examine me!” But a coded message on a crumpled chocolate wrapper whispers “nothing to see here – just a snack.” Time and again, those whispering messages proved more effective.

A Sweet Tooth for Secrets

From the cobblestone alleys of Baroque Europe to the battlefields of modern wars, chocolate has shadowed the world of secret communication in unexpected ways. It has been a carrier of hidden letters, a meeting place for conspirators, a medium for coded ink and signals, a bribery tool, a morale booster, and on occasion, a literal explosive device. In each role, chocolate’s disarming nature – its familiarity and innocence – has been its greatest strength. No one looks twice at a cup of cocoa or a box of bonbons, and that is precisely why, under the right circumstances, they became the perfect foil for intrigue.

It’s a niche slice of history, to be sure. Great battles were not decided solely by candy, and spies didn’t base whole careers on desserts. But it’s fascinating to realize that the bitter complexity of espionage found a home in something as universally beloved as chocolate. Like a detective novel’s red herring, chocolate drew attention one way while hiding something in plain sight. Like a good cipher, it masked meaning with flavor and appearance.

Next time you enjoy a piece of chocolate, consider the rich legacy behind that sweetness. Think of the intrepid couriers who slipped documents into cocoa sacks, or the plotters swapping passwords in a cocoa parlor. Think of weary soldiers writing grateful letters home after a taste of chocolate on the front, and brilliant codebreakers crunching on candy as they unravel enemy secrets. The history of cryptography and secret communication is full of ingenious tools and unsung heroes; improbably, chocolate has been both. It just goes to show: sometimes the key to a great mystery isn’t a magnifying glass or a supercomputer – sometimes it’s a simple cup of chocolate, steaming quietly at the center of the plot, waiting for those clever enough to sip its secrets.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!