The Chocolate Cartel Wars

Smuggling, black markets, informal economies

Midnight, somewhere near the Ghana–Togo border: A battered minibus rattles down a dusty road, its driver nervously eyeing the rearview mirror. The vehicle looks ordinary enough, packed with sacks of cassava and yams – but hidden in a secret compartment beneath the roof are dozens of burlap bags filled with cocoa beans. Suddenly, flashing headlights appear. Uniformed officers from Ghana’s National Anti-Cocoa Smuggling Taskforce flag the minibus to a stop. With a resigned sigh, the driver steps out. In the ensuing search, the officers clamber onto the roof and expose the illicit cargo: sixteen 110-pound bags of cocoa, carefully concealed. It’s the second time this month they’ve caught the same driver on the same route, smuggling Ghana’s “brown gold” out of the country. And he’s far from the only one. In just a few weeks, authorities have seized hundreds of bags of cocoa headed for the nearby Togo frontier – one skirmish in a covert war that spans continents and centuries, the Chocolate Cartel Wars.

A Surge in Cocoa’s Black Market

Cocoa – the raw heartbeat of chocolate – is West Africa’s lifeblood. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) together produce nearly two-thirds of the world’s cocoa beans. For millions of small farmers in these countries, cocoa is not just a crop but an economic backbone. Yet in recent years, a shadow economy has exploded around this humble bean. Smuggling rings spirit cocoa across porous borders under cover of night. Middlemen whisper secret deals in border villages. Countless tons of beans “disappear” from official supply chains, reappearing in neighboring countries’ ledgers as if by magic. It’s a booming black market that authorities are scrambling to contain.

At the heart of this surge in smuggling is a simple economic lure: price. Ghana and Ivory Coast maintain fixed farmgate prices for cocoa, guaranteeing farmers a set rate each season. The policy is meant to protect growers from volatile global markets. But when world cocoa prices soar – as they have in the past two years, reaching their highest levels in over four decades – those fixed local prices start to look like a bad deal. In late 2024, for example, Ghana’s official price to farmers was around $3,000 per ton, locked in earlier in the season. Next door in Côte d’Ivoire, the rate was only slightly higher. But just across the border in Togo – a country without a fixed price, where the market floats freely – traders were suddenly paying the equivalent of $5,000 or more per ton as global prices skyrocketed. Cocoa that could fetch about 1,000 West African francs per kilogram in Ivory Coast might command 1,600–1,700 francs in Guinea or Liberia. For a struggling farmer, that gap is enormous. It can mean the difference between scraping by and finally buying that new motorbike, or affording school fees, or fixing a leaking roof.

And so, an old temptation returned with a vengeance: cocoa smuggling. A Ghanaian farmer in a border village can load up a few sacks of cocoa on the back of a motorbike or in a hired canoe, slip across the frontier, and sell to a Togolese buyer for nearly double the income they’d get from the official channel. For many, the math is too seductive to resist – especially when their livelihoods are on the line. “I have expenses to take care of,” says Joshua Dogboe, a cocoa grower from eastern Ghana’s Volta region. Last year, Dogboe delivered his harvest to Ghana’s state buyer and waited weeks for payment that never arrived; the government-run cocoa board was mired in debt and late in paying farmers. Now, Dogboe admits, if unofficial buyers come with cash on the spot, offering higher prices, he’s ready to sell “quickly, before they disappear.” He knows it’s illegal. He also knows it might be the only way to make ends meet this season.

Dogboe’s dilemma is shared by thousands. Ghana’s Cocoa Board (known as COCOBOD) estimates that in the past two years alone, the country lost nearly half a million tonnes of cocoa to smuggling – roughly a fifth of its total output. That equates to over $1 billion in lost revenue that never passed through official hands. The pattern is similar in Ivory Coast, the world’s top cocoa producer. In late 2023, as a poor harvest sent global prices climbing, Ivorian beans started vanishing over the western border into Guinea and Liberia where buyers were offering juicy premiums. Within months, entire convoys of trucks laden with cocoa were sneaking out of the country. In one dramatic bust early in 2024, Ivorian security forces, tipped off by informants, pursued a trio of trucks along a red-dirt road near the frontier. When they finally stopped them just a few miles from Guinea, they found 100 tons of cocoa in the cargo holds – 1,500 bags of beans likely headed into the black market pipeline.

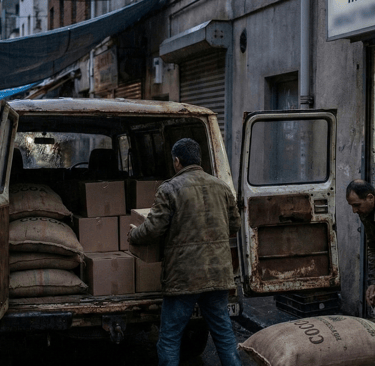

What’s striking is how organized and brazen these operations have become. “It’s not just farmers carrying a few bags on bicycles or motorbikes anymore,” notes Abu Seidu, who leads a cocoa task force in Ghana’s Volta region. “Now you see a heavy-duty tipper truck loaded with cocoa, with a pile of stone chippings on top as disguise,” he explains. During one recent patrol, Seidu’s team stopped a truck that appeared to be transporting gravel from a quarry – only to uncover hundreds of sacks of cocoa hidden beneath the top layer of rocks. “If you catch a truck with 800, 500, or even 200 bags,” Seidu says, “it tells you someone is aggregating the cocoa… It’s now an organized cartel.”

Indeed, law enforcement officials suspect that sophisticated trafficking syndicates are bankrolling much of this trade. No longer is it just enterprising local farmers or penny-ante smugglers on bicycles. According to intelligence gathered in Ghana, some of the most active cocoa-smuggling rings are operated or financed by foreign businessmen and shadowy intermediaries based in Togo and other neighboring states. Investigators have traced links to individuals from Lebanon, China, France, and even Russia, who have set up shop just over the border. These middlemen provide the cash up front to buy large quantities of beans from farmers, arrange the logistics of transport, and then funnel the contraband cocoa into the global market – often mislabeling its origin to evade detection. Once the beans slip into the supply chains of a place like Togo or Guinea, they can be exported legitimately as that country’s “product,” or quietly sold to international buyers who are none the wiser (or perhaps prefer not to ask too many questions about where this sudden bounty of cocoa came from).

The scope and reach of these networks have alarmed authorities. In Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo’s government has declared a “war on cocoa smuggling.” The country’s military has been drawn in, with soldiers deployed along remote border stretches, setting up snap checkpoints on backroads known to be smuggling routes. Special units, like the Anti-Cocoa Smuggling Taskforce, conduct sting operations and surveillance, acting on intelligence about upcoming shipments – like the tip that foiled the minibus in Sagakope with cocoa stashed in its ceiling. In border communities, you might notice new posters plastered on walls and trees, offering rewards for information on cocoa smugglers. One such poster promises whistleblowers a cut of one-third the value of any confiscated shipment – meaning that just tipping off officials about a minibus hiding 16 bags of cocoa could earn an informant nearly $1,800, close to what a typical farmer makes in a whole year. The message is clear: the government is willing to pay handsomely for leads to crack down on this black market.

Ivory Coast, too, has ramped up enforcement. The country’s powerful Coffee and Cocoa Council (CCC), which regulates the industry, has enlisted police and even paramilitary gendarmes to patrol border crossings. The CCC’s director, Yves Brahima Koné, announced a “firm commitment to reduce cocoa smuggling” and has publicly touted successes: more checkpoints, more seizures, more smugglers behind bars. In October 2023, Koné declared that, despite high prices luring beans away, “people are really finding it hard to get cocoa out of Ivory Coast” due to tighter security.

Still, for every truck or canoe intercepted, many others likely slip through. The financial incentives are simply so strong. A veteran Ivorian cocoa buyer in a western border town puts it bluntly: “The farmers themselves earn nothing from smuggling. It’s the middlemen who pocket all the money.” He explains that a smuggler’s agent might pay a farmer a modest premium above the official price – maybe a few extra cents per kilo, which to a poor farmer is enticing – but then that agent turns around and sells the same beans across the border for a much larger profit. In essence, a new class of cocoa contraband kingpins is emerging: people with enough capital to buy up tons of beans at a time, the logistical know-how to move them illicitly, and the connections to resell them internationally. These are the cocoa equivalent of cartel bosses, albeit without the infamous names or violent reputations of, say, drug lords. By and large, the “Chocolate Cartel” prefers stealth and bribes over bullets. But the effect on the formal economy is potentially devastating, siphoning away export earnings from the very countries that depend on cocoa the most.

Seeds of Wrath: A History of Cocoa Smuggling

If all this sounds like a storyline ripped from the modern war on drugs or a Hollywood smuggling caper, it might come as a surprise that cocoa smuggling is hardly new. In fact, the commodity that gives us chocolate has a long, rich history of black-market intrigue. Wherever there have been profits to be made from cocoa, there have been those willing to bend or break the law to get a bigger share of the spoils.

Travel back three centuries to the Spanish Empire in the Americas, and you’ll find one of the earliest “chocolate wars” playing out. In the 1700s, Spain jealously guarded its New World cacao sources – in colonies like Venezuela, where the prized beans from Caracas and Maracaibo were as valuable as gold in European markets. The Spanish crown granted monopolies to chartered companies (such as the Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas) to control the cocoa trade. These companies fixed the prices paid to local growers and forbade any unauthorized selling of cacao to foreign powers. But the local planters bristled under what they saw as unfairly low prices and oppressive rules. And just offshore, lurking in the Eastern Caribbean, were eager buyers: Dutch, British, and French traders who would pay handsomely, no questions asked, for smuggled Spanish cacao.

A clandestine trade blossomed. Venezuelan cacao farmers covertly sent boatloads of cocoa beans to nearby Dutch islands like Curaçao, or to British Jamaica, trading in secret coves and hidden inlets under the cover of darkness. By the mid-18th century, historians estimate that millions of pounds of Venezuelan cacao – some accounts say between three and four million pounds annually – were quietly being siphoned onto the Dutch black market, feeding the burgeoning chocolate demand in Amsterdam and London. This was hotly illegal contraband, and it enraged the Spanish authorities. The monopoly company’s agents and colonial troops would periodically crack down – seizing contraband cacao, arresting smugglers, even executing a few as a warning. But it was a cat-and-mouse game; the coastline was long, enforcement spotty, and the profits too tempting.

In April 1749, tensions boiled over into outright rebellion. Led by a charismatic planter named Juan Francisco de León, Venezuelan cacao growers rose up in anger against the Guipuzcoan Company’s stranglehold and low prices. For years, many had quietly enriched themselves by selling to the smugglers. Now they took to the streets of Caracas, armed and determined to expel the hated company. Part of what fueled their revolt was the conviction that if they couldn’t get a fair price legally, they would damn well get it illegally – or overthrow the system altogether. The rebellion was eventually quashed by Spanish forces, but it forced reforms; the monopoly loosened its grip slightly and raised prices to placate growers. It’s a vivid historical echo of what’s happening in West Africa today: when farmers feel cheated by official channels, the black market offers an outlet – albeit a dangerous one – for their frustration.

Meanwhile, far to the north, in the Anglo-American colonies, cocoa smuggling took on a swashbuckling, piratical flair. In the 1730s and 1740s, New England merchants weren’t just trading codfish and lumber – a few intrepid souls dabbled in illicit chocolate trade. Bostonian traders, for instance, would swap their goods for high-quality cacao from Dutch Suriname or French Martinique, skirting British import taxes and navigation laws. Some even mixed this with the nefarious slave trade, creating a triad of contraband: New England rum and fish -> traded for enslaved Africans in West Africa -> transported to Suriname and exchanged for cacao -> which was then smuggled back to North America or Europe. It was a dangerous game; mutiny, piracy, and prosecution by authorities all lurked as risks. One infamous episode occurred in 1743 aboard the schooner Rising Sun. Laden with a fortune in smuggled cacao (and tragically, fifteen enslaved Africans intended for sale), the ship was seized not by a navy patrol but by greed from within – several crew members mutinied, slaughtering the captain and officers to steal the illegal riches on board. When news of the “cocoa mutiny” leaked out, it shocked colonial society, laying bare how entwined smuggling, violence, and human misery could become in the pursuit of chocolate profits.

From the Spanish Main to New England, chocolate’s first boom centuries ago had a dark underside of subterfuge and bloodshed. Smuggling was, in effect, an early form of arbitrage – buying low in one market and selling high in another – just as it is today for those trucking beans from Ghana to Togo or Ivory Coast to Guinea. It flourished wherever authorities imposed controls or tariffs that created price gaps, and wherever demand for the product was ravenous enough to entice risk-takers.

Even in more recent history, outside the tropical lands of cocoa production, chocolate has spurred black markets in subtler ways. During World War II, for instance, when sugar and chocolate were rationed luxuries in Europe, a thriving underground trade in chocolate sprung up in cities like London and Paris. Allied soldiers’ rations – those iconic GI chocolate bars – often became currency on the streets, bartered for favors or goods, or sold at inflated prices to civilians desperate for a taste of sweetness amid wartime austerity. In postwar England, before candy rationing was lifted in 1953, sweet-toothed Britons whisperingly traded ration coupons or paid a small fortune under the table for extra chocolate for a child’s birthday. Chocolate, innocuous and wholesome in peacetime, turned into contraband under scarcity. And one need only recall the classic images of black marketeers in postwar Berlin trading Nescafé and Hershey bars – luxury items in the rubble of a defeated city – to understand that even in consumer societies, chocolate has held a power beyond mere flavor: it can symbolize normalcy, comfort, even hope, and thus command a premium when officially out of reach.

Conflict Cocoa and the “Cartel Wars” of Today

Back to the present: the renewed wave of cocoa smuggling in West Africa has already drawn comparisons to more notorious illicit trades. Some observers speak of “cocoa cartels” in the same breath as drug cartels. The analogy isn’t perfect – cocoa smugglers aren’t blowing up police stations or waging violent turf wars (cocoa, after all, is a legal commodity for which there’s a perfectly above-board market; it’s the manner of trade that’s illegal here, not the product itself). Yet the term “cartel” isn’t entirely misplaced. The smuggling rings do function like cartels: they collude to control supply routes, they maintain secrecy and corruption networks, and they reap outsized profits off the labor of those at the bottom (the farmers) by exploiting market loopholes. And one could argue that West African governments themselves have formed a cartel of another kind – a benign one aimed at stabilizing prices, but a cartel nonetheless – in an effort to help their farmers and counter the leverage of multinational chocolate companies.

In 2019, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, tired of seeing their farmers remain impoverished while global chocolate giants raked in profits, banded together to create a joint initiative often dubbed an “OPEC for cocoa.” They agreed to coordinate on pricing and introduced a premium called the Living Income Differential (LID) – essentially a surcharge of $400 per ton on cocoa sales, intended to raise farmer incomes. This cooperation formalized in 2023 as the Côte d’Ivoire–Ghana Cocoa Initiative (CIGCI), an effort to present a united front in the market and ensure a better deal for their growers. For the first time, the two rivals – normally competitors for buyers – were acting in concert like a classic commodity cartel.

But even as the two countries fixed higher prices and negotiated with global buyers, the informal economy fought back in its own way. The higher official prices were good news for farmers on paper, but they remained fixed annually and still lagged behind surging world market prices. Meanwhile, the LID premium, disliked by some international traders and chocolate makers, may have had unintended consequences. Some dealers, unwilling to pay the extra $400/ton on Ivorian and Ghanaian cocoa, quietly sought out beans from elsewhere – from Nigeria, Ecuador, or… yes, from neighboring countries where smuggled Ivorian/Ghanaian beans could be laundered as local produce without the premium. In effect, the moment Ghana and Ivory Coast tried to strengthen their hand, the market found a way around it, with the help of the cocoa underworld. The “cartel war” in this sense pits the official producer alliance against the shadowy smuggling cartels, each undermining the other’s strategy.

There have even been hints of geopolitical intrigue. In Ghana, the head of COCOBOD raised eyebrows when he suggested that elements of Russia’s Wagner Group – the infamous mercenary network – were involved in cocoa smuggling in Africa, allegedly buying up illicit Ivorian and Ghanaian beans through proxy traders. The claim, made in 2024, came as Wagner was expanding its footprint in West Africa and looking for new revenue streams amid international sanctions. While hard evidence is scarce and some analysts remain skeptical, the mere suggestion underscores how valuable cocoa has become on the global stage. If there’s truth to it, it wouldn’t be the first time conflict and cocoa mixed: during Ivory Coast’s civil war in 2010–2011, rebel militias controlling the western regions reportedly smuggled tens of thousands of tons of cocoa out through Liberia to fund their arms purchases. Just as “blood diamonds” fueled conflicts in Sierra Leone or Congo, one could speak of “conflict cocoa” in Ivory Coast’s turmoil – a resource to be plundered and traded by warlords. Those former rebels-turned-smugglers became a kind of criminal cartel themselves after the war, using networks of army checkpoints and bribed officials to skim off cocoa profits long into the peace.

The victims of all these shady dealings – past and present – are, at the end of the day, the small farmers and the legitimate economies of producing nations. When beans are sold illicitly, farmers remain in the shadows, often underpaid even by the smugglers, with no access to the benefits that come from selling through official channels (like potential bonuses, pension schemes, or support programs from cocoa boards). They also risk severe penalties if caught – prison sentences of five to ten years in Ghana, for instance, for anyone convicted of cocoa smuggling. That’s a harsh fate for a farmer whose only crime is seeking a better price for his hard-grown harvest. Meanwhile, governments lose tax revenues and foreign exchange earnings, widening national budget holes and, ironically, making it harder for those governments to support farmers or invest in rural development. It’s a vicious cycle: low rural development and poverty incentivize smuggling; smuggling drains revenues; lack of revenues means less money to invest in farmers, which keeps them impoverished and inclined to smuggle.

There are social costs too. The cocoa black market often goes hand-in-hand with other illicit activities. In some cases, child labor and trafficking intersect with these informal networks – traffickers might smuggle vulnerable children from impoverished neighboring countries into Ivory Coast or Ghana to work on cocoa farms, especially if the farms are off the radar of authorities due to illicit trading. And if a farmer decides to sell to a smuggler, they’re unlikely to report or seek help for abused or trafficked laborers, for fear of exposing their own illegal sales. Additionally, a lucrative smuggling trade can breed corruption: local officials or border guards might be bribed to turn a blind eye, undermining governance and the rule of law in fragile communities. A Ghanaian police inspector was arrested last year after he was found escorting a truck packed with contraband cocoa – allegedly ensuring its safe passage for a cut of the profits. These stories sow mistrust, painting law enforcement as complicit, and make honest farmers wonder why they too shouldn’t bend the rules when those tasked with upholding them are on the take.

Battling the Bitter Aftertaste

Faced with a threat to their most precious industry, West African governments and their partners are searching for solutions beyond just crackdowns. While law enforcement and border patrols remain crucial, many experts argue that the real antidote to cocoa smuggling is economic, not just criminal. As one development specialist puts it, “If a farmer can earn a decent living selling legally, the incentive to smuggle evaporates.” In practice, that means raising farmgate prices to more competitive levels, paying farmers on time, and reducing the costs they shoulder for fertilizer, tools, and other inputs.

There have been some moves in this direction. In late 2024, when Ghanaian farmers grew restless and even threatened mass smuggling as a form of protest, the government took notice. Ghana’s finance ministry made the unusual decision to increase the fixed cocoa price mid-season, bumping it up by 12% to appease farmers after Ivory Coast preemptively raised its own price. It was a temporary fix, but it sent a message that farmer voices – and the specter of them taking their crops underground – carried weight. Both Ghana and Ivory Coast continue to pressure big chocolate manufacturers and global commodity traders to pay the LID premium and share more value down the supply chain. Progress is uneven, but the effort highlights a fundamental truth: the chocolate industry at large cannot afford to ignore the plight of its farmers, or else face a breakdown in the sustainability and legality of its cocoa supply.

International partners are also stepping in to help. Switzerland, famed as a chocolate-making hub but with no cocoa trees of its own, has offered technical assistance to Ghana to improve traceability systems. The idea is to use technology (like digital tracking, barcoding of cocoa bags, even blockchain ledgers) so that cocoa from every farm can be followed to its final destination. If fully implemented, that could make it harder for smuggled beans to be laundered into the supply chain undetected – if a batch of beans appears at a port without a traceable origin, alarm bells would ring. But such systems are expensive and complex, especially in remote rural areas where farmers may not even have smartphones. In Ghana, pilot programs are training farmers to use electronic scales and record purchases digitally. Ivory Coast has considered GPS tracking units on trucks hauling cocoa, to ensure they don’t wander off approved routes to clandestine border crossings. These measures, while promising, will require sustained investment and farmer buy-in to be effective.

Another strategy has been community incentives. Ghana’s new bounty reward for informants, for example, essentially tries to turn ordinary citizens and even participants in the smuggling trade into allies of the state by giving them a financial stake in stopping illegal shipments. Early reports suggest a modest increase in tip-offs since the reward posters went up. However, informant schemes can also breed grudges and even violence – a desperate smuggler who suspects a neighbor of snitching might retaliate. Careful handling is needed to ensure this war on smuggling doesn’t turn into neighbor-vs-neighbor witch hunts in impoverished villages.

Perhaps the most nuanced approach is tackling the root cause: farmer poverty and overreliance on a single crop. Diversification programs are being promoted, encouraging cocoa farmers to intercrop with other plants or develop side businesses, so a slump in cocoa price (or being cut off from official buyers) isn’t a ruinous blow. Some NGOs help organize village savings and loan associations, giving farmers a financial cushion and reducing the temptation to accept a smuggler’s quick cash. And there’s a quiet recognition that past anti-smuggling tactics sometimes backfired – for instance, Ghana once offered free fertilizer to boost yields, but canceled the program when bags of fertilizer were found being smuggled out for sale across the border. Now, the government has cautiously reintroduced free farm inputs, hoping that better monitoring will prevent abuse while still giving farmers a boost to their productivity and income.

Will these efforts turn the tide? It’s an uphill battle. As long as a bag of cocoa can fetch even a few dollars more by driving it across a jungle road into another country, someone will be willing to do it. And as long as the world’s chocoholics demand ever more cacao – global consumption keeps rising, from gourmet single-origin dark bars to the steady Halloween candy and holiday treats – the pressure to produce cocoa cheaply remains. In a sense, the informal cocoa economy is the market’s way of correcting an imbalance: if farmers in Nation A are underpaid and buyers in Nation B are overpaying, the invisible (illegal) hand brings the two together via a smuggling route. The challenge for policymakers is to remove the imbalance so that invisible hand doesn’t need to act outside the law.

A Bittersweet Legacy

One might wonder, as they unwrap a chocolate bar or sip a cup of cocoa, why this beloved treat so often seems to carry a bitter aftertaste of exploitation – child labor, deforestation, and now smuggling and cartels. The truth is, chocolate’s supply chain has always been complex and fraught with inequality. The Chocolate Cartel Wars of today are but the latest chapter in a long story of people fighting – sometimes literally – over who gets to profit from this cherished commodity.

From colonial planters skirting imperial decrees to modern farmers defying their governments’ pricing schemes, the protagonists are often the same: those at the bottom rungs trying to claim a fair share of the wealth that cocoa can create. The antagonists, too, follow a familiar pattern: powerful entities (be it colonial companies, corrupt officials, or opportunistic syndicates) determined to maximize their own gain, laws and ethics be damned. Caught in between are individuals simply trying to survive or thrive in the system they’re born into – a Ghanaian farmer weighing whether to sell to an illegal buyer to feed his family this year, or a Venezuelan campesino in 1740 weighing whether to load his mule and sneak off to the Dutch trader who pays in silver coin.

As the crackdowns continue and new countermeasures roll out, the sounds of this silent war echo on: the rumble of an engine at midnight leaving a farm with a forbidden cargo; the hush-hush phone call between a middleman in Lomé and a financier in Beirut arranging the next shipment; the frustrated sigh of an official scanning shipping records for anomalies; and perhaps loudest, the chorus of voices from cocoa villages clamoring that they deserve better for the fruits of their labor.

It is easy to enjoy a piece of chocolate without a thought for the journey of its ingredients. Yet, embedded in that rich flavor is a global drama – one that involves smuggling plots and economic brinkmanship in real-life chocolate wars. The next time you indulge in a truffle or a cup of hot cocoa, consider the far-away struggles that help keep that supply steady and affordable. The world of chocolate isn’t only sweet delight; it’s also clandestine deals on moonlit nights and a fight for economic justice that spans generations.

In the end, the story of smuggling, black markets, and informal economies in chocolate is a reminder that even the most ordinary pleasures often have extraordinary backstories. The battle between the chocolate cartels – both the criminal kind and the cooperative kind – will likely persist until the deeper issues are resolved. Until then, the wars in the shadows rage on, leaving us to savor each bite of chocolate with perhaps a bit more appreciation of the complex tapestry of human endeavor, desire, and ingenuity that makes it possible. The taste is sweet, but the struggle to bring it to our lips can be bitter indeed.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!