The Chocolate Cartographers

Ancient and modern trade routes, maritime maps, shipping lanes, cacao geopolitics

On a humid evening at the port of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, a container ship slips away from the dock, its metal hull groaning under the weight of thousands of burlap sacks filled with cocoa beans. The ship’s route will trace a path westward across the Atlantic, bound for factories in Europe where those humble brown beans will be transformed into chocolate. It’s a journey mapped by winds and currents that echo ancient paths and bygone empires—a voyage that connects jungles to sweet-toothed cities half a world away. This scene, modern as it is, carries echoes of history: for as long as people have craved chocolate, they have been charting new routes on the map to get it. The story of chocolate is, at its heart, a story of exploration and exchange—an epic that spans ancient trade routes, colonial ambition, high-seas adventure, and global geopolitics, all fueled by humanity’s hunger for the “food of the gods.”

Ancient Footprints of Cacao

Long before chocolate became a worldwide obsession, cacao grew quietly in the shaded understory of tropical rainforests. The tree is indigenous to the upper Amazon basin, but by around 1000 BCE it had made its way north into Mesoamerica. In these lands—the cradle of chocolate—cacao found a devoted following. The Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations cultivated cacao not just as a crop but as a cultural cornerstone. They fermented, roasted, and ground the beans to make a potent bitter beverage often spiced with chili or vanilla, creating the earliest form of hot chocolate. This drink was more than a treat; it was a ritual elixir, a status symbol, even a form of currency. In the bustling Maya marketplaces and Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, cacao beans jingled in purses like coins, traded for everything from food to clothing. An Aztec document from the 1500s records that one turkey hen was worth about a hundred cacao beans—a fact that astounded the first Europeans who heard of it.

Yet cacao’s value transcended money. It was interwoven with the sacred. Maya kings were anointed in cacao at birth and venerated with chocolate at ceremonies. The Aztecs believed the god Quetzalcoatl had gifted cacao to humankind, and their emperor Montezuma famously downed cup after golden cup of chocolate to fortify himself. Wherever cacao went, it carried an aura of prestige and mystery. And go it did: ancient trade routes carried cacao far beyond the humid zones where it grew. Maya merchants paddled canoes laden with cacao pods along the rivers of Central America. They trekked overland with sacks of dried beans on their backs, linking lowland cacao orchards with the highland cities that hungered for the coveted beans. This web of trade spread wide. By the turn of the first millennium, evidence suggests that cacao had journeyed northward out of Mesoamerica: chemical traces of cacao have been found in pottery fragments in the desert canyons of New Mexico. How did it get there? Archaeologists theorize a far-flung barter system, the “turquoise trail,” where cacao traveled in exchange for turquoise and other precious goods from the American Southwest. Imagine the scene: a caravan of merchants meeting in a dusty market outpost, one side laying out brilliant blue-green turquoise stones, the other opening sacks releasing the faint aroma of cocoa. Across these cultural crossroads, the flavor of chocolate passed from tropics to desert, becoming a small taste of luxury in a far-off land.

By the 15th century, on the eve of European contact, cacao had created its own geography. Its cultivation was concentrated in equatorial pockets—from the Yucatán and Chiapas down through Guatemala and coastal Honduras—while trade routes fanned outward. Cacao even served as tribute: conquered peoples under Aztec rule paid their overlords in cacao loads, meaning that beans harvested in the humid Gulf Coast plains were trekked hundreds of miles into the Valley of Mexico to fill imperial storehouses. In effect, the Aztecs drew the first “chocolate map” of the world they knew, with roads of commerce radiating from the cacao groves of the south to the royal altars of the north. This map, however, was just the beginning. A far larger, global map of chocolate was about to be drawn—by ambitious newcomers arriving from across the sea.

Charting a Course to Chocolate

In the summer of 1502, Christopher Columbus’s last expedition was slogging its way along the coast of Central America when the explorers came upon a large canoe paddled by Maya traders. The Spaniards clambered aboard the dugout and curiously poked through its cargo of unfamiliar wares. Among the loot were strange almond-like beans that spilled everywhere when a Spaniard overturned a canoeist’s basket. To the surprise of Columbus’s men, the native traders scrambled frantically to gather each bean, as if retrieving scattered gold coins. Perplexed, the Europeans had stumbled on cacao—the currency of the New World. Columbus, failing to grasp the beans’ value or the beverage they could make, wrote them off as a curiosity. He sailed on, unaware that he’d briefly held in his hands a key that would unlock a new passion in the Old World.

It fell to Hernán Cortés nearly two decades later to truly put chocolate on the map for Europe. Cortés arrived in the Aztec capital in 1519 and was greeted by Emperor Montezuma II with a sumptuous banquet, complete with frothing chocolate drinks served in gilded cups. The Aztecs’ esteemed “cacahuatl” (as they called it) was bitter, spiced, and, to Spanish tongues, bewildering at first sip. But Cortés noted how fervently the Aztec nobility prized the drink—and how many cacao beans filled Montezuma’s treasure vaults. As much a schemer as a swordsman, Cortés sensed an opportunity. After toppling the Aztec Empire, he began cultivating cacao in the colonial territories of New Spain (present-day Mexico) and encouraged its use as a trade good. By the 1530s and 1540s, Spanish galleons laden with cacao beans were regularly setting sail from Veracruz, bound for Seville and Cádiz.

These early transatlantic chocolate voyages were nothing short of revolutionary. For the first time, chocolate crossed an ocean, bridging the great geographical divide between its birthplace and the insatiable appetites of Europe. Spanish friars, colonial officials, and merchants all played a part in chocolate’s migration. Legend has it that when the first sacks of cacao arrived in Spain, they were initially met with skepticism—until someone thought to mix the roasted ground beans with sugar and cinnamon, tempering the bitterness and creating a beverage that soon took the Spanish court by storm. A fashionable addiction was born. By the early 1600s, drinking chocolate had become the toast of aristocratic Spain, cherished as a fortifying morning cup or an indulgent afternoon luxury.

Keen to keep this delectable secret (and its lucrative trade) to themselves, the Spanish guarded knowledge of cacao’s cultivation and the preparation of chocolate for many years. Indeed, for much of the 16th century, Spain held a virtual monopoly on European chocolate. But secrets seldom last. The aroma of chocolate wafted beyond Iberia: through marriages, diplomacy, and espionage, other Europeans soon acquired the taste and the beans. In 1615, a Spanish princess wed into the French royal family, bringing chocolate as part of her dowry and introducing it to the Parisian elite. Italian merchants, ever at the forefront of trade, procured cacao via Spanish connections by the early 17th century. Before long, the craving for chocolate spread across Europe like a new craze. Royals, nobles, and clergymen from London to Vienna clamored for a sip of the exotic cocoa drink.

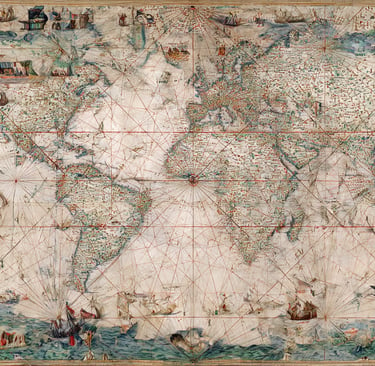

Supplying this demand meant drawing new lines on the map. The Spanish colonies in the Americas ramped up production—plantations of cacao expanded in Guatemala, Venezuela, and Ecuador, all to feed the European market. Transatlantic shipping lanes grew busy with “chocolate ships.” Spanish treasure fleets now sailed not only with bullion and spices, but with tons of cacao beans stashed in their holds, nestled among gold and silver. These ships followed the rhythmic clockwork of the ocean: every spring, a fleet would depart Seville for the New World, and every summer, after loading up with colonial riches (cacao among them), they would race back across the Atlantic on the prevailing Gulf Stream currents, hoping to outrun storms and pirates. On old maritime maps of the 1600s, one can almost see these routes traced out: dotted lines arcing from Caribbean ports back to Spain, the lifelines of an empire sustained by, among other things, its chocolate habit.

Pirates, Smugglers, and the Chocolate Wars

Where there is treasure, trouble follows. And chocolate, once it became a treasure, proved no exception. The high seas of the 17th century swarmed with pirates and privateers drawn to the bounty of the New World, and Spanish cacao shipments quickly became a target. In those tumultuous days, a fortune in cacao could be as prized as a chest of jewels—if one knew what it was. Early on, some plunderers didn’t. There’s an apocryphal tale from 1579: an English privateer boarded a Spanish vessel off the coast of what is now Mexico and discovered a strange cargo of dry, brown beans. Finding no gold, the disgusted raiders tossed the beans overboard and even burned part of the shipment, thinking the Spaniards were carrying sacks of worthless “sheep droppings” as a ruse. Little did they realize they had just consigned literal boatloads of chocolate to the depths. It was a mistake the buccaneers would not repeat for long. As Europe’s love of chocolate grew, the pirates got wise. By the 1600s and 1700s, English and Dutch freebooters prowling the Caribbean learned to recognize the rich, bitter scent of cacao in a captured ship’s hold—and to regard it as precious cargo.

Piracy wasn’t the only challenge to Spain’s chocolate monopoly. Rival European powers wanted in on the cocoa trade by any means necessary. If they couldn’t get enough beans through honest trade, they would steal them or, better yet, grow their own. This led to a burst of botanical intrigue and subterfuge. Smugglers spirited cacao seeds and seedlings out of Spanish territories, despite Spanish laws that threatened violators with harsh penalties. Soon cacao trees were sprouting in unexpected new places on the world map. The Dutch, having established a foothold in northeast South America, cultivated cacao in their colony of Suriname and traded for beans from the Venezuelan coast. The English, after seizing Jamaica from Spain in 1655, found cacao already growing there—planted by Spanish settlers—and quickly expanded production on the island. The French began planting cacao in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and their other Caribbean holdings. Even far across the Pacific, the Spanish themselves inadvertently globalized chocolate: via the Manila–Acapulco galleon trade, cacao crossed from Mexico to the Philippines in the 17th century. The Philippines became one of the first places in Asia to embrace chocolate, as Spanish friars and local farmers planted cacao in the archipelago’s rich soils. In this way, the world’s cacao belt began to extend its reach, moving beyond Mesoamerica into the Caribbean, Asia, and eventually Africa.

By the dawn of the 18th century, chocolate was truly international. In European capitals, the once-secret Spanish treat had become the latest vogue among high society. Chocolate houses were popping up in London, Amsterdam, and Paris—stylish establishments where gentlemen gathered to sip hot chocolate, gossip, gamble, and scheme. At a London chocolate house in 1657, one could buy a cup of the exotic drink for the exorbitant price of 10 to 15 shillings (a week’s wages for a common laborer), so coveted was the cocoa brew. These elegant salons were Europe’s first taste of café culture and they democratized chocolate consumption beyond the nobility—anyone with the coin could partake. As demand rose, the pressure mounted to secure reliable, ample supplies of cacao.

This demand transformed cacao from a niche delicacy into a major commodity, and with that transformation came conflict and intrigue on a global scale. The Caribbean and the coasts of Central and South America became arenas of competition, with colonizers vying for the best cacao-growing territories. There were even “Chocolate Wars” of a sort: not formal wars between nations solely over cacao, but economic battles and occasional skirmishes. A noteworthy episode unfolded in the early 1700s when the Scottish entrepreneur John Law formed the French Mississippi Company, which among other aims sought to monopolize the chocolate trade from Louisiana and the Caribbean. Law’s grand plans collapsed in financial scandal, but they underscored cacao’s new stature in global trade. In the Spanish Americas, indigenous and African laborers toiled on cacao haciendas under often brutal conditions, producing the beans that filled European ships. And at sea, opportunistic privateers commissioned by rival governments harassed Spanish cocoa convoys. Every chest of cacao beans bobbing on the waves now had nations and fortunes tethered to it.

It was in this era that cartographers in Europe began to include cacao on their maps and charts, marking regions known for chocolate production much as they would note gold mines or spice islands. An English map of the West Indies from the 1740s, for instance, labels parts of Venezuela’s coast as the “Caracas cacao” region—today still famous for its fine cocoa. The map of chocolate was expanding rapidly, and no one was more keenly aware of it than the rising industrial powers hungry for raw materials for their growing chocolate industries. Little did they know that the biggest changes were yet to come, on continents that had not yet played a part in chocolate’s story.

Redrawing the Cocoa Map: New Worlds of Chocolate

For roughly 300 years after Columbus, the world’s cacao came almost exclusively from the tropical Americas—where it had originated—and a handful of Caribbean islands. But the 19th century brought a wave of change that would forever shift chocolate’s center of gravity. The twin forces of industrialization and colonial expansion were at work. In the 1800s, technological advances in Europe (like the steamship, railroads, and improvements in processing cacao into cocoa powder and solid chocolate) meant chocolate could be produced on an unprecedented scale. No longer just an aristocratic indulgence, chocolate was becoming a mass-market product—solid chocolate bars, tins of cocoa, and confections for the middle classes. This surge in demand sent the colonial powers scrambling for more cacao, far beyond the traditional groves of Latin America. And so began the great cacao migrations: a concerted effort to plant and grow cacao in any suitable corner of the tropics under European control.

Africa was the new cacao frontier. In an ironic twist of fate, Europeans introduced the New World tree to the Old World tropics. In the 1820s, Portuguese traders and Brazilians took cacao to the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe in West Africa. These tiny equatorial islands, with their rich volcanic soil, proved ideal. By the late 1800s, São Tomé had become one of the world’s top cocoa producers—albeit under horrific conditions, as colonial plantations used enslaved or indentured labor well into the late 19th century. Not to be outdone, the British, French, and Germans established cacao plantations in their African colonies on the mainland. The fertile Gold Coast (modern Ghana), under British rule, was especially promising. In the 1870s, a Blacksmith-turned-farmer named Tetteh Quarshie returned to the Gold Coast from the Spanish island of Fernando Po with cacao seeds and successfully planted them near Accra. His trees thrived, and enterprising local farmers spread the crop widely. By the early 20th century, Ghana was nicknamed “the Gold Coast” not just for its mineral wealth but for the “brown gold” of cocoa—it became the largest cacao producer in the world, astonishing the old plantations of Ecuador and Brazil with its output.

The French, meanwhile, introduced cacao in their West African territories: Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria (under shared British influence in the region), and Cameroon (first German, then French). These places would soon take their own prominent spots on the chocolate map. In Asia too, cacao found new homes. The Dutch cultivated cacao in their Southeast Asian colonies, notably on the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia) by the 1830s. Cacao even reached Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India in small quantities via the British, and parts of Southeast Asia via the Spanish and later Americans (the Philippines remained a chocolate-loving legacy of its Spanish past).

By 1900, the cacao belt encircled the globe, roughly hugging the equator through South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. The implications were profound. For the first time, chocolate production shifted into the hands of many players, breaking the old dominance of Latin America. European and American businesses poured investment into these new cacao lands, and whole economies in West Africa and elsewhere pivoted toward the crop. With expansion came pitfalls: boom-and-bust cycles, crop diseases, and exploitation of workers shadowed the rise of these new plantations. In one notorious scandal of the early 1900s, journalists exposed that the booming cocoa plantations of São Tomé were using forced labor, prompting boycotts by ethical consumers and companies like Cadbury. The episode highlighted how geopolitics and ethics were becoming entangled with the chocolate trade.

From a bird’s-eye view, a map of the world in 1914—on the eve of World War I—would show a vivid new geography of chocolate: West Africa bursting with cacao pods destined for British and French factories, Southeast Asian cacao feeding mostly Dutch and American markets, and the old guard producers like Venezuela, Brazil, and Ecuador still very much in the mix. It was a competitive global supply web, and one that would soon be tested by the fires of conflict and economic upheaval in the 20th century. World wars and the Great Depression rocked commodity markets, including cocoa. Yet even as empires fell and new nations rose, the cultivation of cacao persisted and continued to spread. After World War II, colonialism receded, but the newly independent countries of West Africa kept cocoa at the heart of their economies. Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), in particular, invested heavily in cocoa after its independence from France in 1960; by the late 1970s, Ivory Coast surpassed Ghana to become the world’s leading cocoa producer, a title it holds to this day. The world’s chocolate map had now fully tilted: what started in the Americas had found its new epicenter in Africa.

Modern Chocolate Highways

Today’s chocolate trade is a massive operation that makes the voyages of the Spanish galleons look quaint by comparison. More than five million tons of cocoa beans are produced each year worldwide, the majority flowing out of West Africa in an endless stream of ships and trucks, barges and trains—a global choreography of logistics delivering sweetness to billions. The journey of a modern cocoa bean from farm to chocolate bar is an eye-opening study in globalization.

Consider a single cacao pod harvested in the humid forests of Ghana. A farmer splits open the football-shaped pod to scoop out wet, sticky white pulp encasing the seeds. Over several days, those seeds ferment under banana leaves on the farm, then dry under the tropical sun until they resemble the brown beans recognizable as cocoa. The farmer sells a sack of dried beans to a local buying clerk, which makes its way by truck to a coastal warehouse. From there, the beans are graded, packed into jute bags, and loaded onto a container ship at Tema or Abidjan port. Now begins a oceanic voyage: that ship might sail north, skirting the bulge of West Africa, crossing the busy Atlantic shipping lanes toward Europe. In these lanes, supertankers and freighters trace routes as familiar as interstate highways—sea paths determined by currents, weather, and centuries of shipping tradition. Our cocoa-bearing ship likely heads for the port of Rotterdam or Amsterdam, historic hubs of the cocoa trade.

It’s not a coincidence that the Netherlands is the world’s largest importer and processor of cocoa beans. The Dutch have been in the chocolate business for centuries (they pioneered the cocoa press in the 19th century, revolutionizing chocolate making), and today enormous facilities in Amsterdam and other Dutch ports grind and refine a large portion of the globe’s cocoa into butter, powder, and liquor for chocolate products. So our Ghanaian beans might be offloaded in Amsterdam’s harbor, their arrival just one tiny part of a daily torrent of cocoa pouring into Europe. From there, they could be roasted and ground in a Dutch factory or shipped by rail or barge to chocolate manufacturers in Belgium, Germany, or the UK. In a matter of weeks, the fruits of a small African farm are transformed into glossy chocolate bars on a supermarket shelf in London or New York.

Modern maritime maps of cocoa’s journey are truly global. Major shipping lanes now connect the chocolate supply to demand across hemispheres. West African cocoa travels not only to Europe but also to the Americas and Asia. The United States, another chocolate-loving nation, brings in cocoa beans through ports like Philadelphia and New York (often via Europe or directly from producing countries in Africa and Latin America). In Asia, Indonesia’s sizable cocoa crop might sail to Malaysia or Singapore, where there are large grinding facilities, before heading out again as finished chocolate to markets in Japan, China, or Australia. Thanks to refrigerated containers and swift transport, even finished chocolate confections can be shipped internationally without melting—a feat early chocolate traders could only dream of.

Standing on the bridge of a modern cargo ship, a captain charting a course via GPS and satellite weather updates might feel far removed from the wooden ships of yore following the trade winds. But in a sense, today’s container vessels are the direct descendants of those old galleons and clippers, still moving cacao along the same general corridors, albeit with exponentially greater volume and efficiency. The sea lanes between the Gulf of Guinea and Western Europe, between Latin America and North America, between Southeast Asia and the rest of the world—these are the chocolate highways of our time. And they are busy: at any given moment, there are ships at sea carrying the equivalent of billions of chocolate bars worth of cocoa.

The scale is immense, yet the fragility of this system is an ever-present concern. Global disruptions—whether a pandemic, a conflict, or climate-driven weather chaos—can ripple through the chocolate supply chain. A strike in an Ivorian port or a severe storm in the Atlantic can delay shipments and nudge up the price of cocoa futures in New York or London within hours. In that sense, the maritime maps of chocolate are also maps of interdependence, tying farmers, traders, manufacturers, and consumers into one global network. And like any network, it has its politics.

Cacao Geopolitics: Power and Perseverance

To the casual chocolate lover, a bar of chocolate is a simple pleasure—creamy, sweet, unassuming. But behind the wrapper lies a complex web of geopolitics and power that has been centuries in the making. Cacao, for all its sweetness, has often been entwined with bitter realities of global economics and politics. From the colonial era to the present, control over cacao has conferred wealth and influence, while the lack of control has left many producers struggling.

In the 20th century, newly independent countries in the tropics realized that this little bean was one of their biggest bargaining chips on the world stage. Cocoa became a pillar of economies in West Africa, Central America, and parts of Asia. But reliance on a single crop is a double-edged sword. Cocoa prices on the international market can swing wildly with weather, speculation, or political turmoil, and these swings have real consequences. The “Great Cocoa Boom” of the 1970s, for instance, brought a windfall to producers when a mix of bad harvests and high demand caused prices to skyrocket. Governments of cocoa-exporting nations suddenly had overflowing coffers—some invested wisely in development, others squandered the opportunity. Then came the bust: prices crashed in the 1980s, contributing to economic crises in countries like Ghana and Nigeria. Chocolate, it turned out, had its booms and busts just like oil or gold, and entire nations rode those waves.

No country knows this better than Côte d’Ivoire. The Ivorian economy is so bound up with cocoa that the fortunes of its government, the stability of its rural communities, and its relations with foreign powers all intertwine with the rise and fall of cocoa prices. At times, cocoa has even been a weapon or a prize in conflict. During Côte d’Ivoire’s civil unrest in the early 2000s, control of the cocoa-growing regions became a strategic objective for both rebels and the government. In 2011, during a disputed presidential election, the European Union briefly banned Ivorian cocoa exports as leverage against an incumbent clinging to power—a rare instance of chocolate as an overt tool of international diplomacy. The ban was short-lived, but it underscored how something as everyday as a chocolate bar can have ties to urgent global affairs.

In recent years, two West African nations—Ivory Coast and Ghana—have taken an unprecedented step: banding together to exert more influence over the chocolate industry. Together, these two countries produce over 60% of the world’s cocoa. Tired of seeing their farmers remain poor while multinational chocolate companies reap profits, in 2019 Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire formed a cartel-like partnership some dubbed “COPEC” (a nod to OPEC, the oil producers’ cartel). They introduced a fixed premium on their cocoa sales called a “Living Income Differential,” essentially demanding buyers pay extra per ton of cocoa to boost farmer incomes. It was a bold gambit, evidence that even smallholder cocoa farmers, through collective national action, could push back against the global giants. The move sent shockwaves through the industry and sparked new negotiations about pricing and sustainability. While challenges remain and the global market dynamics are complex, this act of resistance marked a potential turning point—recognition that the people at chocolate’s source deserve a fairer share of its value.

Geopolitics also plays out in quieter ways on the chocolate map. Consider climate change: rising temperatures and shifting rainfall threaten the narrow band of climates in which cacao thrives. Scientists project that by 2050, today’s prime cocoa zones in West Africa may become less suitable, potentially shifting the “cacao belt” to new regions or higher altitudes. Governments and chocolate companies are already eyeing countries like Sierra Leone or areas in Latin America that could become tomorrow’s cacao heartlands. It’s a kind of speculative cartography, drawing the future map of chocolate based on climate models and agronomic research. At the same time, conservationists urge protecting and intensifying cultivation on existing farmland to prevent cacao-driven deforestation of pristine rainforests. Thus, the geopolitics of chocolate now also encompass environmental policy: how to grow more cacao without razing the ecosystems that make Earth livable.

And then there’s the consumer side: Northern consumers, increasingly concerned with ethics, have spurred movements for fair trade and sustainable chocolate. Labels and certifications now dot the packaging, promising that the bar you bought didn’t fuel child labor or raze a jungle or shortchange the farmer. This trend, while driven by consumer conscience, loops back to geopolitics: it pressures producing-country governments and international bodies to enforce labor laws and environmental protections. In effect, chocolate lovers have become inadvertent participants in chocolate geopolitics, voting with their wallets for a fairer supply chain.

The Ever-Evolving Map of Chocolate

From sacred Maya groves to mega-plantations in Africa, from the marketplace of Tlatelolco to the commodity exchange in London, the saga of chocolate has been one of constant movement and adaptation. If we step back and look at the broad strokes, it’s astonishing how dynamic the map of chocolate has been. In just a few centuries, cacao has circled the planet—a feat few other foods can claim with such romantic flair. It’s as if the world has been redrawn by chocolate, each era charting new routes: canoes gliding down rainforest rivers, galleons braving the high seas, steamships cutting travel time across oceans, trains and trucks thundering beans to factories, airplanes carrying boutique chocolates to luxury shops an ocean away.

What makes this story enduringly captivating is that it’s still unfolding. The chocolate map continues to change, responding to the push and pull of human appetites and ingenuity. New countries like Vietnam and Uganda emerge as cocoa producers; entrepreneurs develop high-quality cacao in places off the traditional path, like Hawaii or Madagascar, putting those locales on the radar of artisanal chocolate makers. At the same time, traditional producers like Ivory Coast strive to climb the value chain—investing in local chocolate factories so they export not just beans but finished chocolates, redrawing the trade routes so that more of the journey (and profit) stays in-country. And who knows what the future holds? Perhaps breakthroughs in agriculture will allow cacao trees to thrive in greenhouses in Europe or the US, or genetic research will yield cacao varieties that can grow in slightly cooler climes, redrawing the map yet again. Maybe sustainable practices and local farming will shorten the supply chain, with chocolate being made closer to where it’s consumed from regionally grown cacao.

For now, though, every piece of chocolate we enjoy carries with it the essence of faraway lands and long journeys. The next time you unwrap a chocolate bar, take a moment to reflect on its path: the ancient knowledge of the Maya and Aztec that lies behind its flavor; the bold explorations and risky voyages that brought cacao across the seas; the generations of farmers who have tended the fragile trees in steamy orchards; the vast network of ships, ports, and roads that delivered it to your hands. Chocolate is the product of a thousand stories woven together, a map of human history marked by both dark shadows and bright swaths of creativity and cooperation.

In a world obsessed with speed and technology, the journey of chocolate remains touchingly elemental—a chain of human hands and natural forces bridging jungles and cities. It reminds us that exploration isn’t just the stuff of legends; it lives on in the commodities and cultures that connect us. We are all, in a sense, chocolate cartographers, each time we savor a piece of chocolate and imagine the places it came from. With every bite, we participate in a journey spanning eras and oceans, tracing the lines on that ever-evolving map drawn by the love of chocolate. In the end, that might be chocolate’s greatest gift to us—not just its taste, but the rich tapestry of connections and history it carries, mapping a shared world of delight.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!