The Chocolate Language

Linguistics, terminology, etymology, mythic origins of words

Every chocolate lover knows the bliss of tasting a silky square of dark cacao or sipping a rich cup of cocoa. But hidden in that everyday indulgence is a lexicon of stories as layered and rich as a bonbon assortment. The language surrounding chocolate—its very name, its terminology, even the mythical tales tied to its words—reveals a history of kings and gods, of global journeys and happy accidents. From ancient temples to modern cafes, chocolate’s vocabulary tells a story about human civilization itself. In this long-form exploration, we’ll unwrap the origins of chocolate’s most delicious words, tracing how linguistics and legend have flavored the way we talk about our favorite treat.

Ancient Roots: Cacao in Myth and Language

Long before “chocolate” became a word on anyone’s lips, there was cacao. The cacao tree is native to the tropical Americas, and by 3,000 years ago it was already being cultivated by early Mesoamerican civilizations. The Olmec people of present-day Mexico are often credited as the first to domesticate the cacao plant. We don’t know what the Olmec called it, but they passed their cacao cultivation and terminology to those who followed. The Maya, for instance, prized cacao so highly that it became both a luxury crop and a currency. The Classic Maya word for cacao was recorded as “kakaw” (often written in glyphs as symbols sounding like ka-ka-wa), and cacao beans were used as money—literally small change that could buy food or pay tribute. In ancient Maya art, kings are often depicted drinking cacao, and their ceramic drinking vessels were inscribed with hieroglyphs declaring them to be for kakaw. In other words, chocolate had its own language in the Maya world, written right onto royal cups.

Cacao held deep mythic significance. The Maya offered cacao in rituals and saw the cacao pod as symbolically connected to the human heart, with the cacao drink’s color linked to blood in sacrificial ceremonies. In Mayan tradition, chocolate was more than food—it was communion. In fact, one Mayan Quiché expression, chokola’j, means “to drink chocolate together.” It’s a beautiful notion that the very act of sharing a chocolate drink gave rise to a word about community and togetherness. Some scholars have mused that this could even be an origin of the word “chocolate” itself, as we’ll soon explore. Among the Aztecs of Central Mexico, who inherited the love of cacao from earlier cultures, chocolate was likewise dubbed the “drink of nobles” and was strictly an elite affair. Aztec warriors, priests, and emperors consumed a bitter, spiced cacao beverage known for its invigorating effect. By the time the Aztec Empire flourished in the 15th century, cacao beans were flowing in from tribute-paying regions, filling imperial storehouses alongside gold and jewels.

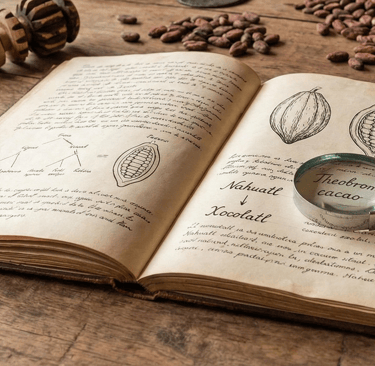

It’s no wonder the Aztecs wove myths around cacao. One popular legend tells that the god Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent deity of wisdom, brought the first cacao tree from paradise and gifted it to humankind. According to this tale, Quetzalcóatl was later punished by the other gods for sharing this divine secret, banished for giving mortals a taste of heaven. The Aztecs thus revered chocolate as a gift from the gods—literally a “food of the gods,” an otherworldly substance. They believed that wisdom and power came from cacao, and warriors drank it for strength. Here we see mythology and language entwine: if cacao was heavenly, to partake in it was to converse with the divine. Centuries later, when European scientists would give cacao a genus name, they chose Theobroma, Greek for “food of the gods,” echoing exactly what the Aztecs and Maya had been saying all along.

From “Xocolatl” to Chocolate: A Linguistic Journey

The very word chocolate is a linguistic confection of its own—a blend of sounds and cultures that crossed oceans. English chocolate comes from Spanish chocolate, which in turn was born during the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the 1500s. But how did the Spanish coin that word? The answer is a bit complicated, and as bitter-sweet as chocolate itself.

For many years, a charming story circulated that chocolate comes from the Aztec/Nahuatl word “xocolatl,” often said to mean “bitter water” (from xococ, sour or bitter, and atl, water). This explanation certainly sounds plausible: the Aztec chocolate drink was bitter, and it was essentially a flavored water of cacao. The idea took hold so firmly that you’ll still find it in books and even the names of trendy chocolate shops. However, modern linguists and historians have peeled back the layers of this tale and found that “xocolatl” might be more myth than fact. In Nahuatl sources from the time of the Spanish conquest, a word like xocolatl is hard to find. The word xococ in Nahuatl actually means sour, not bitter, and was used to describe fermented maize gruels, not the cacao drink. So, if the Aztecs didn’t call their chocolate “bitter water,” where did the word chocolate really come from?

The evidence suggests the Aztec word for the cherished cacao drink was “cacahuatl,” literally “cacao water.” This term is clearly related to cacao (the bean) plus atl (water). It rolls off the tongue similarly to many other Nahuatl words for beverages (for example, atole is a corn gruel, and pulque was octli atl, the agave drink). The Spanish, in their early encounters, used cacahuatl or just cacao to refer to the beverage. But here they encountered a linguistic quirk: in Spanish, caca is a crude word for feces. Understandably, Spanish colonizers were a bit uncomfortable marketing a delectable new drink with a name that began with “caca.” One theory proposes that this vulgar coincidence spurred a search for an alternative name.

Enter the mingling of languages: The Spanish had allies and subjects among various indigenous peoples, including the Maya further south. The Maya often consumed their cacao hot, unlike the Aztecs who usually drank it cold. In the Mayan languages, one word for hot is chokol. According to a theory popularized by scholars Sophie and Michael Coe, the Spanish cleverly combined the Maya term chokol (hot) with the Nahuatl atl (water) to forge a new hybrid word: “chocolatl.” In essence, they may have created a name that meant “hot water” to describe the hot chocolate they grew fond of, sidestepping the awkward caca. This mixed-linguistic origin story is compelling because it mirrors the mixed cultural reality of colonial Mexico: Spanish conquerors adopting an indigenous drink, modifying it to their tastes (adding sugar and spices, serving it warm), and even naming it through a fusion of indigenous languages. It’s a delicious piece of historical wordplay: chocolate as a product of cross-cultural blending, just like the drink itself.

Another intriguing possibility emerges from the Nahuatl language alone. Some linguists have pointed out that many modern dialects of Nahuatl (and related languages) use words like chikolatl or chokolaj for chocolate, suggesting the original Nahuatl term might have had a “ch” sound instead of “x.” Why would that be? Nahuatl has a word chicoli (or chikolli), which refers to a stick or tool for stirring—such as the wooden whisk used to froth chocolate. A recent hypothesis posits that the original term could have been “chicolatl,” meaning “stirred drink” or “beaten drink,” highlighting the distinctive preparation of chocolate with a foaming stick. Imagine an Aztec chocolatier whisking the cacao mixture to a foam and naming the concoction after the very action that made it delicious. This theory aligns nicely with how integral frothing was to the experience—Mesoamericans prized the foam atop their chocolate. If chicolatl was indeed the word, it would have easily been heard by Spanish ears as the familiar-sounding chocolatl, leading to the Spanish chocolate.

In truth, we may never pinpoint the exact moment or mechanism by which chocolatl became the go-to term in New Spain (colonial Mexico). It could be the Spanish heard a version with ch from some dialect or neighboring language. Or they might have engineered it themselves from pieces of words, as the Coes argue. What we do know is that by the late 1500s, Spaniards in Mexico were calling the drink “chocolate,” and they carried this word back to Europe along with shipments of cacao. The first European references to chocolate as a drink appear in the 16th century, and by the 17th century chocolate was a fashionable beverage name in Spanish, Italian, French, and English parlors. The word was exotic but easy enough to say, and it spread even faster than the treat itself. Each language gave it a slight twist—French turned it to chocolat, the Italians cioccolata, the Germans Schokolade. In every tongue, it became synonymous with a little piece of Eden in a cup or on a plate.

Cacao vs. Cocoa: A Tale of Two Words

While chocolate was making its grand tour of Europe, the earlier word cacao took a quieter path—and underwent its own transformation. The Spanish word cacao came directly from indigenous languages (likely from the Maya or Olmec via Nahuatl cacahuatl). It referred to the cacao bean and the raw material used to make chocolate. Early English texts in the 1600s did use the word cacao (sometimes spelled cacoa or cacaoa) when describing the exotic beans from the New World. However, as English speakers became more familiar with the product, a funny thing happened: cacao got munged into cocoa.

Linguistically, cocoa is essentially an English accident. Scholars believe that English traders and writers heard the word cacao but transposed the letters (perhaps thinking it was pronounced similarly to coco as in coconut). By the late 17th century, English texts were routinely spelling it cocoa. The two vowels in the middle flipped places, and somehow this misspelling stuck. It’s a bit ironic: a whole industry today distinguishes between cacao (usually referring to the raw bean or minimally processed nibs) and cocoa (often meaning the processed powder or mass-produced products). But etymologically, they are the same word—cocoa is just cacao in a quirky mirror. English is one of the few languages that made this switch; most others kept a form of cacao. The persistence of cocoa in English might also be because it was easier to say and already vaguely familiar (the word coco in Spanish, meaning coconut, was known, and cocoa sounds warm and cozy). By the time of Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary, “Cocoa” was defined as the dried seed of the cacao tree used to make chocolate.

Interestingly, as knowledge of chocolate grew, the scientific naming of the plant paid homage to its divine reputation. In 1753, the great botanist Carl Linnaeus assigned the cacao tree the Latin name Theobroma cacao. We’ve noted Theobroma means “food of the gods,” a nod both to the heavenly taste and perhaps to indigenous lore of divine origin. And cacao was enshrined in science as the species name, ensuring that term would never disappear completely. In recent years, especially among artisanal chocolate makers and nutrition circles, there’s been a small renaissance of using cacao (in English) to refer to the pure, raw product, as if reclaiming the original word from which cocoa sprang. So next time you ponder buying “cacao nibs” instead of “cocoa nibs,” remember: you’re really circling back to a 3,000-year-old term, reconnecting with the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec who first gave us this gift.

A World of Chocolate Words

As chocolate culture blossomed worldwide, it brought forth a bouquet of new terms, each with its own story. The language of chocolate expanded beyond the basics of cacao and chocolate to include the processes, people, and confections that define our experience of this treat. Understanding these terms is like learning the dialect of a chocolate lover. Let’s sample a few of the most flavorful entries in the chocolate lexicon:

Chocolatier – This French-origin word literally means a person who makes or sells chocolate (chocolat, plus the -ier suffix for a profession). It entered English in the early 20th century as fine European-style chocolate making took hold. To call someone a chocolatier evokes images of a craftsman, a bit of Old World artistry behind the candy counter. The rise of the chocolatier reflects how chocolate shifted from a homemade drink or apothecary’s mixture into a gourmet art.

Conching – Smooth chocolate as we know it today owes its texture to a process called conching, invented in 1879 by Swiss chocolatier Rudolph Lindt. The word conch comes from the Spanish concha, meaning shell. Lindt’s early conching machine was a tank that looked like a giant seashell in which chocolate liquor (ground cacao mass) was stirred and aerated for hours. This “conch shell” mixer gave its name to the process. Before conching, chocolate was coarse and gritty; afterward, it became lusciously smooth. Thus, a term from the ocean was repurposed into chocolate language. If you ever see “conched for 72 hours” on a chocolate label, now you know the poetic origin of that term.

Temper – To make a chocolate bar snappy and shiny, chocolatiers must temper the chocolate, carefully controlling its temperature to arrange the cocoa butter crystals. The term temper here is just a common English word meaning to moderate or bring into balance (the same root as “temperament”). While not exotic in origin, it’s an old word that found new significance in the chocolate world. When you hear of “tempered chocolate,” it’s all about the language of chemistry meeting culinary craft—balancing something’s “temper” to make it stable.

Criollo, Forastero, Trinitario – These are the names of the primary varieties of cacao beans, and they carry a legacy of colonial history. Criollo is Spanish for “native” or “of the colony” (literally “Creole”), and in cacao it refers to the prized ancient varieties first cultivated in Central America. True criollo cacao is delicate, flavorful, and was the original chocolate of kings, but it’s finicky to grow. Forastero means “foreigner” or “outsider” in Spanish, and it was the name given to hardier cacao that came from “elsewhere” – in practice, the Amazon basin. Forastero became the bulk crop of African and Brazilian plantations (it’s more robust and higher-yield, but generally less nuanced in flavor). When a natural hybrid of Criollo and Forastero emerged on the island of Trinidad in the 18th century (after a storm decimated criollo orchards and new plantings crossed with imported forastero), it was dubbed Trinitario after its island of origin. These terms reflect how European colonizers categorized cacao much like people – natives, foreigners, and mixed – a little linguistic capsule of New World history. To this day, chocolate experts speak of criollo beans in reverent tones, and the very words hint at old tales of exploration and agriculture.

Praline – Today a praline might mean a filled chocolate bonbon in Belgium, a caramelized nut in France, or a creamy pecan patty in New Orleans. But the word’s origin is distinctly aristocratic. In 17th-century France, the personal chef of a certain Marshal Du Plessis-Praslin invented a crunchy almond-and-caramel sweet. He named the confection for his patron, the Marshal – hence praline (originally praslin). The recipe evolved and spread; French settlers took it to Louisiana, where pecans replaced almonds and cream was added, creating the Southern praline. Meanwhile, in Belgium, praline came to mean those elegant filled chocolates (since one of the first Belgian chocolate makers, Jean Neuhaus, adopted the term for his filled bonbons in 1912). What a journey for a word: from a nobleman’s kitchen through continents and centuries, now broadly associated with chocolate indulgence in various forms.

Ganache – Silky, rich chocolate ganache (that mixture of chocolate and cream at the heart of truffles and cakes) has an origin story as smooth as its texture. Legend holds that in the 19th century, a young apprentice in a Parisian pâtisserie accidentally spilled hot cream into a bowl of chocolate. His furious master shouted “Ganache!” – a French insult meaning “idiot” or “fool.” Facing the hot mess, the chefs found that the chocolate and cream, instead of ruining, had emulsified into a glossy, velvety mixture. What began as a mistake became a cornerstone of dessert craft. In a wry twist, the very word for “fool” became the name of a genius invention. Next time you bite into a chocolate truffle and the center melts in your mouth, you’re tasting a happy accident immortalized in language.

Truffle – Speaking of truffles, why do we call those chocolate spheres by the name of a prized fungus dug up by pigs in the forest? The answer lies in appearance. Sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s, as confectioners were experimenting with rolling ganache into bite-sized balls, someone had the idea to dust them in cocoa powder (or sometimes ground nuts). The result was a lump of chocolate that looked strikingly like a dirt-covered truffle mushroom. The whimsical name stuck. A simple metaphor—it looks like a truffle, let’s call it a truffle!—gave us a word that now instantly means “decadent chocolate ball” to anyone with a sweet tooth. The chocolate truffle’s name is a tiny tribute to the power of culinary imagination: even language is an ingredient in creating allure.

Gianduja – This term may be less familiar unless you’re a Nutella fan or an Italian chocolate aficionado. Gianduja (or gianduia) is a blend of chocolate and hazelnut paste, invented in the Piedmont region of Italy during the Napoleonic era. With British blockades causing cocoa shortages, resourceful chocolatiers in Turin extended their precious chocolate supply by mixing it with finely ground local hazelnuts, creating a delicious new concoction. They named it after Gianduja, a jovial masked character in Piedmontese carnival folk theater who represented the archetypal local peasant. Legend has it that during a Carnival celebration around 1865, chocolate makers distributed hazelnut-chocolate treats wrapped in foil depicting Gianduja’s face, cementing the association. Thus, a comedic figure from Italian culture lent his name to a recipe born of hardship but destined for greatness. Today gianduja is revered, proof that even constraints (and a bit of humor) can enrich the language of chocolate.

Chocoholic, Chocolate Box, and other cultural terms – As chocolate ingrained itself in modern life, new words and idioms sprouted in the vernacular. In the 20th century, English speakers invented chocoholic as a playful way to describe someone addicted to chocolate (patterned after “alcoholic”)—a testament to how consuming chocolate was humorously likened to a delightful dependency. The phrase “like a kid in a candy store” captures chocolate’s place in childhood bliss, while “life is like a box of chocolates – you never know what you’re gonna get,” a line from Forrest Gump, became a metaphor for life’s surprises. In British English, calling something “chocolate-box” (as in “a chocolate-box village”) means it’s picture-perfect and perhaps a bit too quaint or pretty—an allusion to the idyllic paintings that adorned chocolate boxes in Victorian times. Even love hasn’t escaped chocolate’s linguistic sway: how many of our expressions of affection, from heart-shaped boxes to chocolate-dipped strawberries, rely on the unspoken language of chocolate to convey sweetness?

Myths, Metaphors, and the Ongoing Story

Tracing the linguistics and lore of chocolate words shows us how tightly language, culture, and beloved foods interweave. Each term carries echoes of discovery, conquest, innovation, and joy. When we say the word chocolate today, we invoke ancient Mesoamerican tongues and the voices of Spanish conquerors; we summon up myths of gods and the experiments of chefs; we hint at bitterness and sweetness all at once. Few foods have a vocabulary so romantic and storied.

The mythic origins behind chocolate’s words continue to enchant us. We still refer to chocolate as a gift from the gods (just check any Valentine’s marketing), an almost sacred indulgence. We tell and retell the legend of Quetzalcóatl’s divine generosity and perhaps feel a tiny connection to those ancient rituals when we savor a cup of hot cocoa on a cold night. The terminology of chocolate-making, from conching to tempering, reminds us that human ingenuity transformed a bitter seed into a confectionary art, and that each innovation left its mark in language. The fact that a slip of the hand gave us ganache, or that an aristocrat’s name lives on in praline, adds a sense of whimsy and humanity to the candy we love.

What’s also striking is how chocolate’s language spans the globe. It is inherently multicultural: cacao might hail from the Olmec or Maya, chocolate from a Nahuatl-Maya-Spanish mashup, gianduja from Italian lore, Schokolade and chocolat from European adaptations, and so on. Yet all these words center on the same essence—the same cherished substance that conquers all hearts. In learning the etymology of chocolate terms, we end up learning a little world history and anthropology along the way. It’s a gentle reminder that simple pleasures often hide rich complexities.

And the story isn’t over. As chocolate continues to evolve in our era—from single-origin craft bars to sustainably traded cacao—new phrases and concepts join the lexicon: bean-to-bar, fair trade, cocoa percentage, grand cru chocolate. The language of chocolate grows just like a living tree, sprouting new expressions with each generation of chocolate lovers and makers. Who knows what new chocolate words await us in the future? Perhaps a century from now, linguists will marvel at how chocoholic or bean-to-bar entered common speech.

In the end, the “chocolate language” is one of indulgence and imagination. It’s the shared vocabulary that lets us praise and savor one of life’s great delights. Next time you enjoy a piece of chocolate, consider the words that melt alongside it on your tongue. From kakaw whispered in ancient prayers to chocolate exclaimed in delight today, these words are part of the flavor. The language of chocolate is yet another reason why this food is special—every bite is a taste of history, myth, and linguistic artistry. And that is truly something to savor.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!