The Cocoa Gold Rushes

Boomtowns, Speculation, Fortune-Seekers, and the Market Frenzies That Shaped History

From Sacred Bean to Colonial "Brown Gold"

Long before chocolate bars lined supermarket shelves, the seeds of the cocoa tree were treated as treasures. In ancient Mesoamerica, the Maya and Aztecs consumed cocoa in bitter, spiced drinks and even used the beans as money. According to Spanish chroniclers, a handful of cacao beans could purchase a simple meal, and around 100 beans might buy you a turkey hen. In a literal sense, money grew on trees in those societies. This early reverence for cocoa set the stage for its explosive journey onto the world market.

When Spanish conquistadors encountered the Aztecs in the 16th century, they were amazed to see these “almonds” (as they called the cocoa beans) being used as currency and in royal ceremonies. The Spaniards developed a taste for the chocolatl drink and soon began shipping cacao back to Europe. At first, chocolate was an elite secret, sipped by Spanish nobles and monks. But word of its wonders spread. By the 1600s, cocoa had become colonial “brown gold.” Spanish colonies in the New World, especially in Venezuela and Ecuador, established cocoa plantations to meet Europe’s growing demand. Cacao beans from the New World became a lucrative trade, second only to precious metals for the Spanish treasury.

This newfound value was not lost on interlopers. In 1579, off the Pacific coast, English privateer Francis Drake captured a Spanish galleon laden with cacao. The story goes that his crew, unfamiliar with the bitter beans, tossed the cargo overboard, mistaking it for worthless sheep droppings. They had unwittingly jettisoned a fortune. As decades passed, pirates and smugglers learned their lesson: cocoa was worth its weight in silver. Dutch and British freebooters regularly raided Spanish cacao shipments, and a thriving cacao smuggling network grew. In Venezuela, “cacao boomtowns” like Caracas and Puerto Cabello prospered on this trade. Wealthy plantation owners there were nicknamed the Gran Cacao – a playful moniker for the nouveau riche whose wealth came from cocoa rather than gold. By the eighteenth century, Venezuelan cacao beans were among the most prized in European markets, leading the Spanish crown to establish a monopoly company to control their trade. Cocoa, once a sacred bean, had become a global commodity, and it was turning planters, merchants, and empires into fortune-seekers.

Yet, behind the boom lay a darker reality. The labor that made cocoa profitable in these early plantations was often forced. Enslaved Africans were brought to work the cacao haciendas of Venezuela, New Spain, and the Caribbean. The pursuit of “brown gold” was brutal: tropical diseases, punishing heat, and long hours plagued the workforce. Cocoa’s first gold rush thus enriched European merchants and colonial elites while the enslaved and indigenous laborers paid a heavy price. This troubling foundation would echo through later chapters of cocoa’s history, as cycles of boom and bust continually intertwined wealth and hardship.

The 19th-Century Chocolate Revolution

For much of the 1700s, chocolate remained a luxury indulgence – a rich drink for aristocrats or a medicine for the ailing. That began to change in the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution met the cocoa bean. A series of inventions transformed chocolate into an affordable treat for the masses. In 1828 a Dutch chemist devised the cocoa press, a machine that squeezed out cocoa butter and left a fine cocoa powder. This made it easier to mix chocolate with water or milk, and crucially, it made chocolate production more efficient. Entrepreneurs like J.S. Fry in England took the next step, combining cocoa powder, sugar, and melted cacao butter to mold the first solid chocolate bars in 1847. Not long after, Swiss innovators Daniel Peter and Henri Nestlé added condensed milk to create milk chocolate in the 1870s. Suddenly, chocolate wasn’t just for sipping in gilded salons – it was a snack that middle-class families and even kids could enjoy. Demand for cocoa beans exploded as candy went mainstream.

This surge in chocolate appetite set off a scramble for supply. Europe’s confectioners and nascent chocolate companies – Cadbury, Nestlé, Lindt, Hershey and others – needed reliable, huge quantities of cocoa. Think of it as a new energy rush, akin to a gold rush but to feed candy factories. Until about 1850, the world’s cocoa mostly came from a patchwork of tropical American sources: Venezuela’s plantations, Ecuador’s coastal orchards, Brazil’s Bahia region, and the Caribbean islands (like Trinidad and Dominica) where cocoa trees grew under the humid canopies. Now, with the market growing, every cocoa-producing region kicked into high gear, and new regions were eyed for cultivation.

One epicenter of the 19th-century cocoa boom was Ecuador. By mid-century, Ecuador (which had gained independence from Spain) realized its coastal climate was ideal for cacao. Small farmers and businessmen alike planted cacao trees across the fertile Guayas river basin. The world’s hunger for chocolate was so great that by the 1890s, cacao made up over half of Ecuador’s exports. The port city of Guayaquil became a thriving boomtown, its docks piled high with burlap sacks of cocoa beans destined for New York, Amsterdam, and London. An upper class of cacao exporters arose – Ecuadorian “cacao barons” who built mansions and founded banks with their profits. They called the cacao bean “pepa de oro,” or grain of gold. For a few glorious decades, Ecuador was the world’s leading cocoa producer, its flavor-rich Arriba variety coveted by chocolate makers everywhere.

South of Ecuador, Brazil also saw a cocoa rush in its Bahia state. Pioneers had introduced cacao to Bahia’s rainforests in the late 1700s, but it was in the late 1800s that Brazilian cocoa really boomed. By the turn of the 20th century, the region around the town of Ilhéus was flush with cacao wealth – a tropics-tinted mirror of a California gold rush town. Plantation owners in Bahia, often called “colonels,” lived extravagantly off “brown gold.” Their rivalries and romances became the stuff of Brazilian legend and literature; novelist Jorge Amado later immortalized this golden age of cacao in stories of obsession, violence, and greed amid the cacao groves. For Bahia and Ecuador alike, the cocoa boom brought both prosperity and the seeds of future turmoil, as monoculture wealth often does.

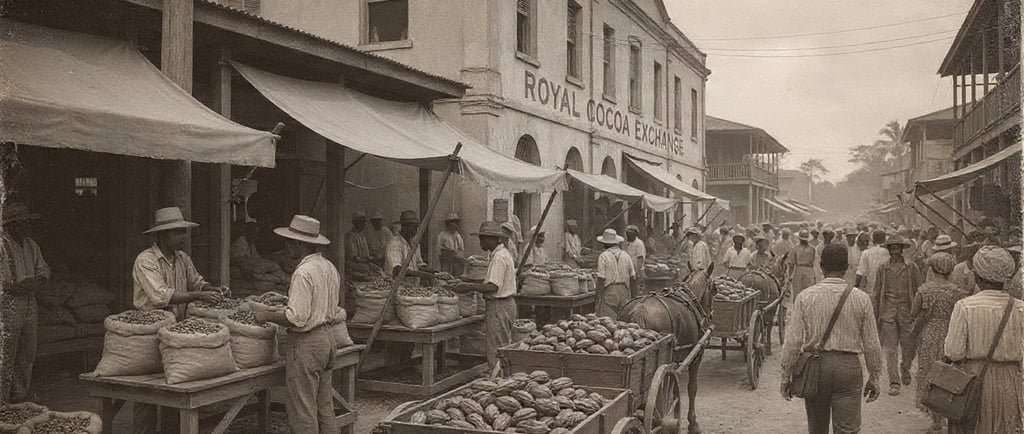

As production raced to satisfy Europe’s sweet tooth, a new phenomenon emerged: adulteration and speculation in cocoa. Cocoa and chocolate were valuable enough that some unscrupulous dealers started cheating customers. In 19th-century Britain, it was discovered that some “chocolate” products contained odd fillers – everything from powdered dried peas to ground brick dust – to stretch the costly cocoa. This food fraud scandal spurred reforms (and gave Quaker-owned brands like Cadbury a chance to shine by emphasizing their pure cocoa). Meanwhile, in the trading houses of London, cocoa was becoming a financial commodity. By the 1850s and 60s, traders would gather in city coffeehouses to buy and sell future shipments of cocoa beans, essentially betting on the next harvest’s price. These informal trades grew into organized cocoa auctions at the London Commercial Sale Rooms by late century. One could say the spirit of the cocoa gold rush moved off the jungle frontier and into the heart of global finance. Cocoa was now not just a crop but a market, subject to the feverish whims of investors. And as with any rush, what goes up must one day come down.

West Africa's Cocoa Frontier

Just as Latin America’s cocoa bonanza began to mature, a new frontier opened – one that would come to dominate the world of cocoa: West Africa. In the late 19th century, European colonial powers introduced the cocoa tree to their West African territories, imagining neat plantations supplying the empires. But what actually happened was both remarkable and unprecedented: local African farmers themselves embraced cocoa with entrepreneurial fervor and planted it far and wide, kicking off one of history’s most dramatic agricultural booms.

The Gold Coast (modern Ghana) offers a vivid example. In 1879, a blacksmith named Tetteh Quarshie returned to the Gold Coast from the Spanish island of Fernando Po, stealthily carrying a few cocoa pods. He planted these seeds on his farm outside Accra. Those trees flourished, and word spread of this promising new crop. Before long, other farmers obtained seeds (some from Quarshie’s stock, others via missionaries) and began raising cocoa trees in the forested heartland of the Gold Coast. The climate was perfect and the timing fortuitous: global cocoa demand was still rising, and European buyers were eager for new sources, especially after a fungal blight and economic woes hit Brazil and Ecuador in the early 20th century. Villagers in the Gold Coast – everyone from tribal chiefs to humble families – started carving new farms out of the rainforests, planting thousands, then millions of cocoa trees. It was a cocoa rush in every sense. By 1910, a mere three decades after Quarshie’s experiment, the Gold Coast was exporting a staggering 40,000 tons of cocoa a year, suddenly becoming the largest cocoa producer on the planet. One British official marveled in 1938 that this growth “has no parallel in the world,” noting that in just forty years Ghana (then the Gold Coast) went from zero to supplying about two-fifths of the world’s cocoa – and all of it grown by tens of thousands of small, independent African farmers.

Other West African colonies followed suit. In Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Ivory Coast, local farmers saw what wealth cocoa could bring and launched their own planting sprees in the early 20th century. By the 1920s and 30s, West Africa’s smallholders dominated the global cocoa trade, eclipsing the old producers of Latin America. What made this especially unique was the largely grassroots nature of the boom. Unlike earlier cocoa frontiers that relied on slave labor or corporate plantations, West Africa’s cocoa boom was driven by peasant farmers investing their own sweat equity. Entire families would move to virgin forest zones, clear land, and plant cocoa seedlings, hoping that in a few years the trees would yield a crop big enough to pay for new houses, school fees, or additional land. Cocoa became known as a “cash crop” par excellence – one could literally grow money on trees, and many African farmers did just that, fueling a new rural middle class.

Of course, the European powers still found ways to profit. They controlled shipping, processing, and prices to a large extent. And not all was idyllic for the African growers: as cocoa farms proliferated, oversupply loomed, and world prices began to sag (more on that in the next section). Moreover, even this chapter had its exploitation – in the Portuguese African islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, cocoa plantations in the late 1800s used indentured labor that was scarcely different from slavery. This sparked an international scandal in the early 1900s when humanitarian campaigners (and some outraged chocolate manufacturers like Cadbury) exposed the horrible conditions under which "chocolate slaves" toiled. Bowing to pressure, major British chocolate companies stopped buying São Tomé’s cocoa by 1909, shifting even more sourcing to the Gold Coast and Nigeria, where cocoa was grown on family farms rather than by forced labor. Thus, the West African cocoa rush was accelerated not just by good farming, but also by a moral boycott that steered business its way.

By the mid-20th century, two West African nations – Ghana and its neighbor Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) – would account for an outsized share of world cocoa. And it wasn’t just a colonial story. When Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence in 1957, it was a land built on cocoa wealth; the crop provided the bulk of foreign earnings and funded infrastructure and education. Ivory Coast, under President Félix Houphouët-Boigny after its 1960 independence, pursued a policy of aggressively expanding cocoa and coffee production. He encouraged migrants from poorer, landlocked African countries to come help clear Ivory Coast’s forests and plant cocoa. New boomtowns sprouted in Ivory Coast’s western forests as farmers – both Ivorian and immigrant – rushed in to stake their claim in the cocoa boom. By the 1980s, Ivory Coast would surpass Ghana as the world’s top cocoa producer, a title it holds to this day. In some Ivorian villages, it wasn’t uncommon to hear stories of humble farmers becoming “cocoa millionaires” practically overnight when a good harvest coincided with high global prices. Entire cities like Daloa and Abidjan grew in prosperity on the back of cocoa exports, mirroring the way San Francisco boomed in the California Gold Rush.

Yet these later African cocoa rushes also carried their share of strife. As Ivory Coast’s cocoa frontier expanded, it gobbled up vast tracts of virgin rainforest – a process often likened to a land rush. By the 2000s, competition over land and the rights of immigrant farmers became a flashpoint, contributing to ethnic tensions in Ivory Coast that eventually fueled civil conflict. In Ghana, rapid expansion gave way to the need for replanting aging trees, and farmers sometimes struggled with diseases and soil depletion after decades of single-crop cultivation. The cycle of boom and bust was setting in, just as it had in Latin America. But before we get to the “bust” part, we must examine how volatile the cocoa market became once it was truly global.

Booms, Busts, and War

As the 20th century progressed, cocoa proved to be a textbook example of a boom-and-bust commodity. Each time a new region ramped up production – be it Ecuador in the 1890s or Ghana in the 1920s – it initially enjoyed high prices (a boom) until the flood of new supply eventually caused prices to crash (the bust). These cycles could be ruinous for those who jumped in late or took on debt to invest in cocoa. In Ecuador, for instance, the golden years of the cacao boom ended abruptly around 1916 when devastating fungal diseases (with ominous names like Witches’ Broom) hit the plantations, at the very moment that cheaper African cocoa was glutting the market. Ecuador’s production collapsed, and the country’s economy nosedived into a crisis; many wealthy cacao families went bankrupt. The once-bustling wharves of Guayaquil fell quiet as the global cocoa trade’s center of gravity shifted to Africa. It was a cautionary tale: cocoa fortunes could vanish as fast as they appeared.

On the world stage, cocoa prices began seesawing with wider events. In the 1910s, the disruptions of World War I and the boom of roaring ‘20s kept chocolate in high demand, but they also introduced instability. By the late 1920s, overproduction was driving cocoa prices to extreme lows. The situation reached a breaking point during the Great Depression. As economic turmoil spread worldwide in the early 1930s, the price offered for cocoa beans sank so much that many West African farmers could not even cover their costs. In despair, some farmers burned or abandoned their cocoa farms. In the Gold Coast, growers famously organized a “cocoa hold-up” in 1930-31: essentially a farmers’ strike where they refused to sell their beans to British trading firms unless they got a better price. Mountains of cocoa piled up unsold as farmers held out for relief. The colonial government eventually intervened with minor concessions, but the incident revealed how cocoa – once a symbol of easy wealth – had become a source of economic anguish for those at the bottom of the supply chain when the market turned against them.

Efforts were made to tame the wild cocoa market. In the 1930s and 1940s, colonial administrations in Ghana, Nigeria and other territories set up marketing boards to stabilize prices. These boards bought cocoa from farmers at fixed rates and handled export sales, aiming to prevent the complete collapse of farmer incomes during busts (though critics noted they also conveniently allowed governments to tax farmers by paying them less than world prices during booms). Such mechanisms did offer a measure of stability. And after the Depression and war years, cocoa saw another uptick. In the aftermath of World War II, rationing ended and consumer demand for chocolate surged back. By 1947, with economies recovering, cocoa prices quintupled compared to wartime levels. For a brief period, there was talk of a chocolate shortage – candy companies scrambled to secure enough beans as war-ravaged plantations struggled to catch up to peacetime demand.

However, true to the cycle, high prices encouraged more planting around the globe. By the 1950s and 60s, cocoa production was expanding not only in West Africa but in new locales like Southeast Asia. Countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, noticing the success of African producers, began to cultivate cocoa on a larger scale (particularly Indonesia, where small farmers on the island of Sulawesi launched a mini cocoa rush in the 1980s). With so many beans flowing into warehouses, the overall trend from the mid-1950s to the early 1970s was a gradual decline in price. Chocolate became ever more affordable for consumers, which was great news for chocoholics but a constant challenge for farmers trying to earn a decent living. Many producers had to reckon with a sobering truth: unlike a true gold or diamond mine, a cocoa tree keeps producing every season, so oversupply was a chronic risk. As one economist quipped, the cure for high cocoa prices is high cocoa prices – because they inevitably lead to overproduction that then causes low prices.

By the late 1960s, major cocoa-producing nations – many of them newly independent – grew frustrated with this boom-bust treadmill. In 1962, Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast and other exporters formed the Alliance of Cocoa Producers, hoping to wield collective power to support prices, similar to what oil nations were attempting with OPEC. International Cocoa Agreements were negotiated in the 1970s to set up buffer stocks and quotas to prop up prices. But such efforts had limited success; the cocoa market often proved unruly and resistant to control. In fact, the 1970s brought a cocoa boom of a different sort – one driven by global economic forces that no single cartel or board could tame.

The Modern Cocoa Rush: Speculation and Sustainability

In the 1970s, the world experienced a commodity price explosion, and cocoa was swept up in the frenzy. Inflation was high, and raw materials of all kinds were suddenly seen as good investments. Between 1971 and 1977, the price of cocoa beans skyrocketed more than tenfold, reaching levels never seen before. By 1977, cocoa hit around $5,000 per metric ton (an astronomical price for the time), shattering old records. A media panic erupted about the soaring cost of chocolate bars. Newspapers warned of a coming “chocolate bar crisis” – the same 5-cent candy bar of the 1960s was now costing several times more, and some feared it could become a luxury item again. This speculative boom was driven partly by real supply issues (bad weather hit some crops, and diseases affected Brazil and others) and partly by big investors piling into commodity markets. It was as if cocoa had become the new gold for a moment, with traders in London and New York shouting buy and sell orders for cocoa futures as frantically as if they were trading oil or gold bullion. Some made fortunes; others got burned when the bubble inevitably burst in the early 1980s, as new production from Asia and a lull in demand led prices to fall back.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, cocoa prices ebbed and flowed in a narrower band, but the game was still on: every few years, a wave of speculation or a supply scare would send prices jumping, only for them to settle down again. In those years, the center of gravity of cocoa production continued shifting. Ivory Coast became the undisputed king of cocoa, achieving harvests well above a million tons a year. Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Indonesia rounded out the top producers. The supply glut often kept prices low, which was great for big chocolate manufacturers who enjoyed cheaper raw materials, but challenging for farmers. Many smallholders in Africa and Asia remained poor, leading to persistent problems like reliance on child labor – kids helping on family farms because hiring paid labor was too costly – and environmental concerns as farmers pushed into new forests to plant more cocoa trees (since planting more was often the only way to increase income when prices were low).

Amid these struggles, the spirit of the cocoa gold rush found an odd new home on the trading floors. A legendary episode unfolded in 2010 that seemed ripped from a financial thriller. A British commodities trader named Anthony Ward decided to make a bold play: he quietly amassed a gigantic stockpile of cocoa beans, eventually controlling an estimated 240,000 tons – about 7% of the world’s annual cocoa production – through purchases on the London exchange. His move was an attempt to corner the market, creating an artificial shortage to drive prices up so he could sell at a profit. The scheme was so audacious that when the press got wind of it, they nicknamed him “Chocfinger,” after the Bond villain Goldfinger known for hoarding gold. And indeed, for a time Ward’s stratagem sent ripples of panic through the market. Cocoa futures spiked; chocolate makers fretted that some mysterious force was driving up their input costs. It was perhaps the most dramatic market frenzy in cocoa since the 1970s, and it showed that even in the digital age, this age-old commodity could inspire bold, almost romantic gambits to make a fortune. In the end, Ward’s cocoa corner gradually unwound (regulators and market forces ensured no lasting monopoly), but not before reminding the world that the game of cocoa speculation can be as wild as any gold rush of old.

And what of the cocoa farmers during these modern rushes? In truth, many on the ground did not see proportional gains from short-term price spikes. The supply chain from bean to bar is long: middlemen, exporters, processors, and big chocolate brands all take their cut. In West Africa, when prices briefly surged due to the Chocfinger squeeze or weather disruptions, farmers saw some increase in pay, but it was often temporary. By the mid-2010s, a paradox emerged: even as consumers were buying more chocolate than ever and even paying higher prices for gourmet cacao or single-origin bars, many cocoa growers continued to live in poverty. This has spurred new conversations about fairness and sustainability in the industry – a modern twist to the old boomtown narrative. There’s talk of a “sustainable cocoa rush,” where companies and NGOs encourage planting high-yield, disease-resistant trees and paying farmers premium prices for quality or organic beans, in hopes of creating a stable, prosperous cocoa economy that doesn’t ride the brutal rollercoaster of booms and busts. Some young entrepreneurs and even youths in places like Nigeria and Ghana have begun referring to cocoa farming as the new avenue for success – a kind of second cocoa rush, but this time focused on smart farming and ethical practices. Whether this can truly reshape the market remains to be seen.

As of the mid-2020s, the cocoa market is again in an upswing. In 2023, global cocoa prices shot to their highest level in over 40 years, fueled by droughts, plant diseases, and strong chocolate demand in Asia. Industry experts spoke of a “global cocoa squeeze” as warehouses reported low stock levels. Headlines noted that the previous record high from 1977 (during that wild ’70s boom) had finally been broken. For cocoa farmers who could still tend healthy crops, it was a boon – some earned a windfall that year. But for consumers, it meant pricier chocolate bars and confectioners contemplating smaller sizes or higher prices. Once again, the pattern asserted itself: high prices prompted talk of farmers expanding their plantings, perhaps pushing the agricultural frontier further into remaining forests of West Africa or encouraging new plantations in places like the Philippines or Papua New Guinea. In other words, the cocoa gold rush is not merely a thing of dusty history books – it’s an ongoing saga.

Sweet Dreams and Bitter Realities

From the Aztec marketplaces where cacao beans changed hands as currency, to the rainforests of Africa where farmers felled trees in hopes of cultivating prosperity, the story of cocoa has been one of frenzied highs and crushing lows. It’s a tale where boomtowns rise and fall on the fickle price of a humble bean, where fortune-seekers take the form of Spanish conquistadors, Ecuadorian exporters, African pioneers, and even Wall Street traders. In these “cocoa gold rushes,” some found sweet success – building cities, companies, even nations on the back of chocolate – while others tasted only bitterness, whether it was the enslaved laborers of colonial cacao farms or the small farmer struggling when prices plummet.

Yet, this saga has undeniably shaped history. Cocoa trade knit together continents; it helped finance colonies and then bolstered newly independent countries. It spurred technological innovation in food processing and played a part in early financial markets development. Cocoa booms altered landscapes, driving migration and deforestation in equal measure. Even culturally, the pursuit of chocolate’s main ingredient left its mark – inspiring literature, prompting ethical reforms (as in the fight against slave labor), and highlighting the interconnectedness of our world. Consider that a simple chocolate bar on a store shelf today carries within it the legacy of all these market frenzies and human dramas: the pirate who burned a sack of beans at sea, the plantation baron who dueled rival growers, the Ghanaian villagers who struck it rich planting trees, and the trader in a skyscraper betting on the next price spike.

For the general audience who loves chocolate, knowing this backstory adds a new layer of appreciation. The next time you unwrap a chocolate bar, think of the centuries of adventure behind its sweetness. Realize that chocolate has seen wars and wonders: it was sipped by Aztec emperors and European kings, fought over by colonists and capitalists, and cultivated by generations of hopeful farmers across the tropics. The cocoa bean may be small and bitter on its own, but it has fueled dreams as grand as any gold nugget. And like gold, it has a way of igniting human passions – for better or for worse.

Today, efforts are underway to make the cocoa industry more equitable and resilient, so that the booms aren’t quite so manic and the busts not so devastating. The idea is to create a sustainable cycle where farmers can prosper without chasing the wild swings of the market, and where chocolate lovers can indulge without guilt. Whether that vision is achievable will be the next chapter in the story. But if history teaches us anything, it’s that cocoa will continue to captivate and confound. There will always be a bit of the gold rush spirit in chocolate’s journey – the gambles, the innovation, the sweet rewards and bitter lessons. And that is what makes the story of cocoa, the world’s favorite treat, not just a tale of goodies and desserts, but a grand human saga of ambition, imagination, and resilience. The cocoa gold rushes may change form, but they’re never truly over – they simply await the next generation of fortune-seekers drawn by the promise of chocolate gold.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!