The Great Chocolate Fraud

Inside an Industry’s Secret Scandal

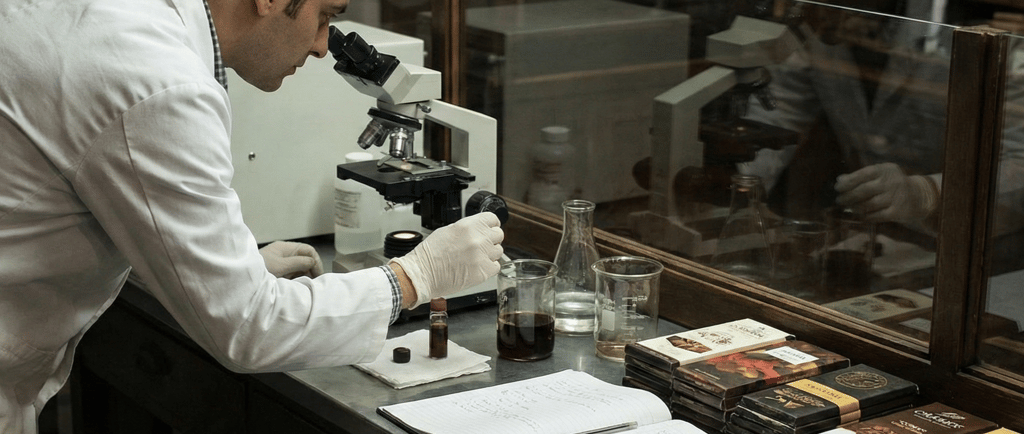

In a quiet laboratory tucked behind a gourmet chocolatier’s shop, a chemist carefully tests a selection of “premium” chocolate bars. What she discovers sends shockwaves through the confectionery world: not all that glitters is cacao. Some of these luxury-labeled bars, priced and marketed as the finest chocolate, are hiding a dark secret. Ingredients don’t match their labels – from exotic origins that seem suspect to flavor profiles that hint at something off. It’s the first clue in an unfolding mystery that will lead a food-safety sleuth and an industry whistleblower through secretive factory backrooms and international markets, all to expose a silent scandal at the heart of our favorite treat.

A Chemist’s Suspicion

Under the shop’s ambient light and the hum of lab equipment, the chemist notices anomalies. One bar, advertised as single-origin dark chocolate, contains unexpected compounds under analysis. The ratios of cocoa butter are wrong, and traces of oils that shouldn’t be there turn up in the test results. Could a 70% cacao bar be bulked up with something cheaper? Her findings aren’t a one-off fluke – they echo a larger pattern. In fact, recent research suggests that about one in ten food and drink products worldwide is adulterated or mislabeled. Chocolate is no exception, especially the high-end bars that command a premium price for purportedly ethical or rare ingredients. The more money at stake, the greater the temptation to cheat. As one industry analyst notes, food fraud often boils down to getting a higher price for lower quality – the same motive behind scandals like mislabeled beef or counterfeit olive oil. Now, it seems, the bean-to-bar bonbons and artisanal dark chocolates might be part of this troubling statistic.

Alarmed by the lab results, the chemist contacts a trusted ally – a veteran food safety inspector known for his dogged investigations. This food-safety sleuth has chased fraud in everything from olive oils to truffle imposters, and he agrees this chocolate case warrants a closer look. Soon, they are poring over chocolate bar labels and supply chain papers, comparing cacao origins and ingredients lists with what the lab found. The deeper they dig, the more it becomes clear: the chemist’s discovery is the tip of a very large (and very cocoa-dusted) iceberg.

The Whistleblower’s Tip-Off

Just as the sleuth and chemist begin their inquiry, a cryptic message arrives from overseas. It’s from an industry insider – a whistleblower who has worked for years in a large chocolate export company. Using careful language, the insider hints at systematic deceit: cocoa beans from ordinary farms relabeled as prized “single-reserve” lots, and shipments of bulk cacao quietly mixed with rarer beans to inflate profit. The whistleblower recounts a troubling practice: “They’d take sacks of our average beans and slip a few premium ones on top for show,” he says, “then mark the whole lot as fine flavor cacao from a special origin.” In essence, buyers were paying for top-shelf quality but receiving a diluted product – a blend that was part genuine, part imposter.

This under-the-radar mislabeling resonates with the sleuth’s own research. Historically, chocolate fraud has deep roots. In fact, as far back as the Aztec empire, cacao beans were so valuable they were used as currency – and counterfeiters of the time molded fake beans out of clay and other materials to trick buyers. Modern chocolate fraudsters are a bit more sophisticated, but no less bold. Today’s counterfeit cacao schemes include substituting lower-quality beans than advertised or mixing in cheap ingredients (like vegetable oil or fillers) into what is sold as pure chocolate. The whistleblower’s tip suggests that such practices aren’t isolated incidents; they may be surprisingly common in certain corners of the industry, hidden behind glossy wrappers and marketing hype.

Emboldened by the insider’s information, the sleuth and chemist devise a plan. They will follow the chocolate’s trail from bean to bar, literally. This means visiting warehouses where beans are graded and sold, testing batches for purity, and even going undercover at a chocolate expo where a source hints that dubious dealers broker “gourmet” cacao that isn’t what it claims to be. Each step peels back another layer of deception.

Secrets in the Supply Chain

One major revelation comes in a bustling port city’s warehouse district. Here, the team observes how beans from different farms and countries are stored and shipped. In theory, a bag labeled “Ecuador – Arriba Nacional, Grade 1” should contain exactly that famed variety of cocoa beans. But their investigation finds that the labels don’t always tell the truth. In one case, genetics don’t lie: a sample of beans purportedly from a single-origin lot in Peru shows DNA markers that don’t match Peruvian cacao at all. A lab specializing in cocoa genomics helps confirm this through cutting-edge tests that can pinpoint a bean’s origin by its genetic “fingerprint”. It appears some exporters have been blending average-quality beans with premium ones and mislabeling the origin to charge higher pricesmentalfloss.com. This fraud not only cheats chocolate makers and consumers – who pay top dollar for a distinctive origin flavor that isn’t really there – but it also harms honest farmers. Smallholder cocoa farmers growing true fine varieties lose out when counterfeit “origins” flood the market, driving skepticism and lowering the value of authentic premium crops.

The complexity of the global cocoa supply chain makes it ripe for these tricks. Cocoa passes through many hands – farmers, collectors, exporters, processors – and at each step there’s room for something to go awry if unscrupulous players are involved. The lack of strict enforcement in some regions further enables misrepresentation. As our sleuth discovers, even certifications like “organic” or “fair trade” can be gamed. An organic or fair-trade label commands higher prices, and Ecovia Intelligence warns that such sustainably-branded products are among the highest risk for fraud because of that premium. For example, fair trade cocoa might be mixed with conventional cocoa down the line, or beans grown with high pesticides could be passed off as organic. The end result is a web of deceit in which traceability is lost – unless someone is actively looking, who would know that a “Dominican single-estate organic cacao” bar actually contains a cocktail of beans from unknown sources?

Our whistleblower provides a critical piece of evidence: shipping records and internal emails from his former employer that detail suspicious relabeling. In one email chain, a manager writes, “We’ll use the Ghana stock for that European order – just tag it as ‘Single Origin Ivory Coast’ and ship ASAP.” Such a swap not only violates trust but could breach food import regulations. It explains why the chemist’s tests in the lab flagged unexpected profiles in bars that were supposedly exclusive to one region.

Cheaper Ingredients, Costly Lies

Mislabeling cocoa origin is one form of deceit; outright adulterating the chocolate itself is another. The deeper the investigation goes, the clearer it becomes that some “fine chocolate” bars have been cut with cheaper ingredients to stretch profits. In a covert visit to a small chocolate manufacturing plant (one that a source suggested might be tampering with recipes), the sleuth observes something troubling. Workers add a mysterious pale solid into a vat of what should be pure cocoa butter and cocoa mass. Later, a sample of that ingredient is analyzed: it’s vegetable fat, likely palm oil-based. By law in many regions, a small amount of alternative vegetable fat (up to 5%) is allowed in chocolate, but it must be declared on the label. Using more than that – or failing to disclose it – is fraud. And beyond the legalities, adding cheap fat dilutes the rich cocoa taste and texture that true chocolate lovers expect. It’s exactly what some big chocolate companies controversially lobbied for in the past. (In fact, in the early 2000s, European regulations began allowing up to 5% non-cocoa vegetable fats in chocolate, despite outcry from purists. Around the same time, even venerable manufacturers like Cadbury faced accusations of using alternative fats in place of authentic cocoa butter.)

The chemist recalls how one of her tested bars showed an unusual fat content: now she knows why. Someone had been cutting corners, replacing expensive cocoa butter with a cheaper substitute and hoping consumers wouldn’t notice. The flavor was slightly off, maybe a bit waxy on the palate – a far cry from the melt-in-your-mouth feel of real couverture chocolate. By labeling these bars as “premium dark chocolate” despite the filler, the producers deceived customers and gained an unfair edge. This is food fraud at its core: a consumer thinks they’re getting a pure, high-quality product and pays accordingly, but the reality is a diluted, phony version.

It’s not just fats, either. Other instances of adulteration uncovered include cocoa powder cut with cheaper powders. One common trick is blending cocoa powder with carob flour – a low-cost lookalike that can mimic cocoa’s color and taste when mixed, and is hard to detect without advanced analysis. An unsuspecting baker or chocolate lover using such cocoa might never realize their product is part impostor. Each of these shortcuts boosts profit margins for the fraudsters but cheats the consumer of the quality they paid for.

Counterfeit Confections on the Market

As the investigation widens, our sleuth follows the trail of fraud beyond mislabeled ingredients to a more familiar sight: counterfeit chocolate bars on store shelves. These aren’t just misformulated chocolates, but outright fake branded products. In a downtown street market, he finds a stall selling what appear to be famous-brand chocolates – including a “Wonka Bar” that sparks his curiosity. The Wonka Bar, beloved from fiction, isn’t actually made by the licensed brand anymore, so any Wonka bars for sale are immediately suspect. Upon closer inspection, the packaging is slightly off-color and the text printing looks low-quality – red flags that it’s a forgery.

It turns out fake “Wonka” bars have been flooding some markets, along with counterfeit bars for brands that are otherwise in vogue. In 2023, the U.K.’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) sounded the alarm on a surge of fake branded chocolate bars – including bogus Wonka Bars and a spurious line of “Prime” chocolate bars (the latter trading on the name of a popular energy drink). These counterfeit bars are often made or repackaged by unregistered businesses operating in the shadows. Hygiene and safety regulations are flagrantly ignored, and buyers truly don’t know what they’re getting. As one FSA official put it, you might think you’re getting a great deal on a fun chocolate, but “you don’t know what is in them… There could be a food safety risk, especially for those with food intolerances or allergies”.

Those words proved painfully true. Last year, dozens of fake Wonka Bars were seized after authorities discovered they contained undeclared allergens – ingredients like nuts or milk not listed on the label. For anyone with a severe allergy, a single bite of those fraudulent chocolates could have meant disaster. And that’s not the only horror story: in one especially shocking case, a counterfeit chocolate product from China was found infested with live worms, little white larvae crawling out of the supposedly delicious treats. French authorities ultimately seized 10 tons of these low-grade counterfeit chocolates in 2013, worth over $300,000 on the black market. The fakes had mimicked the packaging of famous brands like Nestlé and Ferrero Rocher, fooling many customers until the unsanitary truth quite literally wriggled into the light.

What drives this unsettling trade in fake chocolate bars? Again, it’s the lure of profit. Consumers will pay a premium for prestige brands or novel products, and counterfeiters know it. By copying the wrapper and logo, they can trick people into handing over money for what is essentially chocolate shoddy – made with subpar ingredients, or even unsafe ones, in secret facilities. The criminal network behind such fakes treats food safety laws as inconveniences to be evaded. For them, it doesn’t matter if the chocolate contains too much emulsifier, or industrial wax, or no real cocoa at all. Meanwhile, legitimate companies suffer reputational damage when knock-offs bearing their name make people sick or disappointed.

Victims of the Chocolate Con: Health and Heritage

As the sleuth and his allies compile their evidence, it becomes clear that the stakes in this “great chocolate fraud” go far beyond some fancy bars or a few consumers paying too much for too little. Public health is on the line. The adulteration of chocolate can introduce ingredients that some people can’t safely eat – like the undeclared allergens in those fake Wonka bars. Imagine a parent giving what looks like a normal chocolate bar to a child with a nut allergy, unaware that a shady operation made it with cheap nut paste as filler. The result could be a life-threatening reaction. Even when allergens aren’t an issue, unsanitary production (as seen with the worm-infested candies) risks foodborne illness. And consider the heavy metals concern: independent tests in recent years have found concerning levels of lead and cadmium in many dark chocolate products – including premium and organic brandsreuters.com. While those metals originate from soil and manufacturing processes rather than intentional fraud, they further shake consumers’ confidence. If even the high-end chocolate bars might quietly contain harmful substances, whom can you trust?

On the other end of the spectrum are the cocoa farmers and honest chocolate makers who become collateral damage in this fraud. When a gourmet bar is “cut” with cheap ingredients or misrepresented, the honest producers are undercut. Farmers who toil to produce high-quality, sustainably grown cacao depend on the premium that true fine chocolate commands. But if buyers start doubting label claims – suspecting that Madagascar* origin might just be a marketing ploy, or that “75% cacao” might not mean much – the market for fine cacao erodes. In regions known for heirloom cocoa varieties, there is a cultural heritage at stake as well. The names Chuao, Porcelana, Criollo – these once guaranteed a certain prestige and taste. Fraudsters hijacking those names for mediocre cocoa not only cheat consumers, they dilute the heritage and reputations that took generations to build. As one expert observed, “If these new tests work as planned, consumers will be able to make better-informed decisions about their chocolate purchases” – and hopefully preserve the value of authentic sourcesmentalfloss.com. Until then, the burden falls on vigilant actors to police the truth.

The whistleblower, himself from a family of cocoa farmers, laments what he’s seen. “My father grows cacao the traditional way,” he tells the team, “fermenting it just right, taking such pride. But he gets pennies. Meanwhile I saw traders mixing his beans with others and selling a story about ‘legacy cacao’ to naive buyers. It made me sick.” His courage in coming forward stems not just from seeing consumer deception, but from knowing the pain of farmers whose livelihoods are eroded by these scams.

Craving Transparency: The Path Forward

By the end of this far-reaching investigation, the evidence of a silent scandal in the chocolate industry is overwhelming. Armed with lab analyses, shipping documents, and firsthand accounts, the food-safety sleuth compiles a report for regulatory authorities. The FDA in the United States had already begun paying closer attention – in early 2025, it flagged suspicious chocolate products in the market, classifying it as a case of adulteration-related food fraud. Now, with concrete details in hand, agencies like the FDA and international counterparts can dig deeper and possibly bring charges against the worst offenders. Governments and industry groups are waking up to the issue; experts call for stronger audits and supply chain transparency to restore trust. New technologies offer some hope: DNA fingerprinting of cocoa beans, as we’ve seen, can authenticate a bar’s true origin, and advanced spectroscopy can detect filler ingredients in cocoa powder in a flash. But these solutions need wider adoption and can be costly.

Ultimately, the Great Chocolate Fraud raises tough questions about truth and transparency in our treats. Consumers understandably feel betrayed – if you can’t trust the label on a $10 artisanal bar of chocolate, what does that say about our food system? The answer, according to experts, isn’t to give up chocolate, but to demand honesty and accountability. That means pushing companies for more information about their sourcing and production, and supporting those that voluntarily share data (for example, some craft chocolate makers publish detailed sourcing reports each year, listing farms and prices paid). It also means regulators stepping up enforcement and cracking down on food crimes with real penalties.

For now, chocolate lovers can take a few steps to protect themselves and support integrity in the industry:

Buy from reputable makers or sellers: Well-known or transparent chocolatiers are less likely to risk their reputation with fraud. If a deal on “rare origin” chocolate seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Read the labels closely: Look for telltale signs like “chocolate flavored” instead of just “chocolate” – this can indicate use of substitutes. In the EU, a label must state if vegetable fats other than cocoa butter are added. Unusual ingredient names or vague language can also be red flags.

Trust your palate and instincts: If a so-called premium bar tastes waxy, overly sweet, or just odd, it might not be authentic chocolate at all. Some counterfeit or adulterated chocolates have subtle differences in texture or packaging quality. Don’t hesitate to contact the manufacturer if something seems off.

Stay informed: Follow food safety news and alerts. Agencies often publish warnings about known counterfeit products (like the fake Wonka bars). Report suspicious products to authorities – your tip could save someone from harm.

Know your chocolatier: If possible, buy direct from bean-to-bar makers who provide information about their cocoa farmers and processes. As one chocolate expert advises, the more transparent and detailed the story a chocolate company offers, the more likely it is that their product is genuine and ethically produced.

From a once-quiet lab behind a chocolate shop to the far-flung plantations where cacao is grown, this journey has shone a light on an unseen side of the chocolate trade. The Great Chocolate Fraud is a cautionary tale that reminds us how easily trust can be eroded when oversight lags and greed takes hold. Yet, it’s also a rallying cry. By unmasking the deception, the hope is that consumers, industry insiders, and regulators alike will join forces to ensure the future of chocolate is honest – one where every creamy bar and delicate truffle is exactly what it claims to be, from the first silky bite to the last.

Contact

info@menloparkchocolatecompany.com

© 2025 Menlo Park Chocolate Company. All rights reserved.

Subscribe to receive special offers and to hear about new product drops!